Eleven Temples And A Dargah On A Small Street. Living The Heritage On Kamaraj Road Bangalore

The commercial district that is a part of Shivajinagar is very loosely bordered by St John’s Church Road in the north, Kamaraj Road on the East, Dispensary Road in the south, and Seppings Road in the west. Seppings spills into the heart of Shivajinagar—the ever-interesting Russel Market. And across the street from it is the imposing St Mary’s Basilica, where the devout worship at a statue of Mary that is dressed in a sari.

Jul 05, 2022, 17 13 | Updated: Jul 12, 2022, 11 34

The 4.5 km walk from Koshy’s Cafe on St Marks Road to Cooke Town takes about an hour. Two, if you linger on Kamaraj Road. It is easy to linger on Kamaraj Road (Cavalry Road before it was renamed in the 70s).

In an abandoned pre-Independence building on Kamaraj Road, well within the heartbeat of Bangalore cantonment, an abandoned chair sits at the empty doorway.

It is a beautiful chair, that has seen better days. I am quite sure that there are technical words to describe its design, but I still appreciate the intimacy of its backrest, sweeping elegantly to meet the advanced baby bump of a gibbous seat cushion.

The chair is upholstered in silver. Maybe it’s satin…why not.

It looks like a servant from an Indian Downton Abbey—one who lost his gruntle—might have stolen it, out of spite.

Maybe the “dorai”, (freely, lord of the manor), had refused to give him dowry money for his daughter’s wedding. And now, one of the dorai’s family has to sit on a wooden crate at the dinner table.

The chair lies unattended probably because the seat is breached…by someone who dropped a bowling ball, or maybe a fat Viscount—in one corner.

It appears that the silver upholstery implies something, because next to this chair is an out-of-context wooden drawer, recently spray-painted in silver. Maybe this is the silver lining for the chair.

A friendly, toothless individual stares curiously as I take pictures with my iPhone.

He tells me that the chair has a past.

“Antique, sir,” he informs me.

I detect a sliver of Scots in his accent.

I ask him about his accent.

“Yes sah!” he barks, “I served in World War 2. Europe. My officers, all Scottish.”

He looked old enough to have served as a young teenager in the war. I ask him how he knew the chair was an antique piece.

He points diagonally down the street, at the Qurio City Shop.

Then he lost all curiosity in me, tilted his head in dismissal, and began to excavate his ear.

I walked over to the The Qurio City Shop. Although I had driven past it for decades, I had never stopped to check it out. Every time though, I have wanted to. There’s something compelling about it.

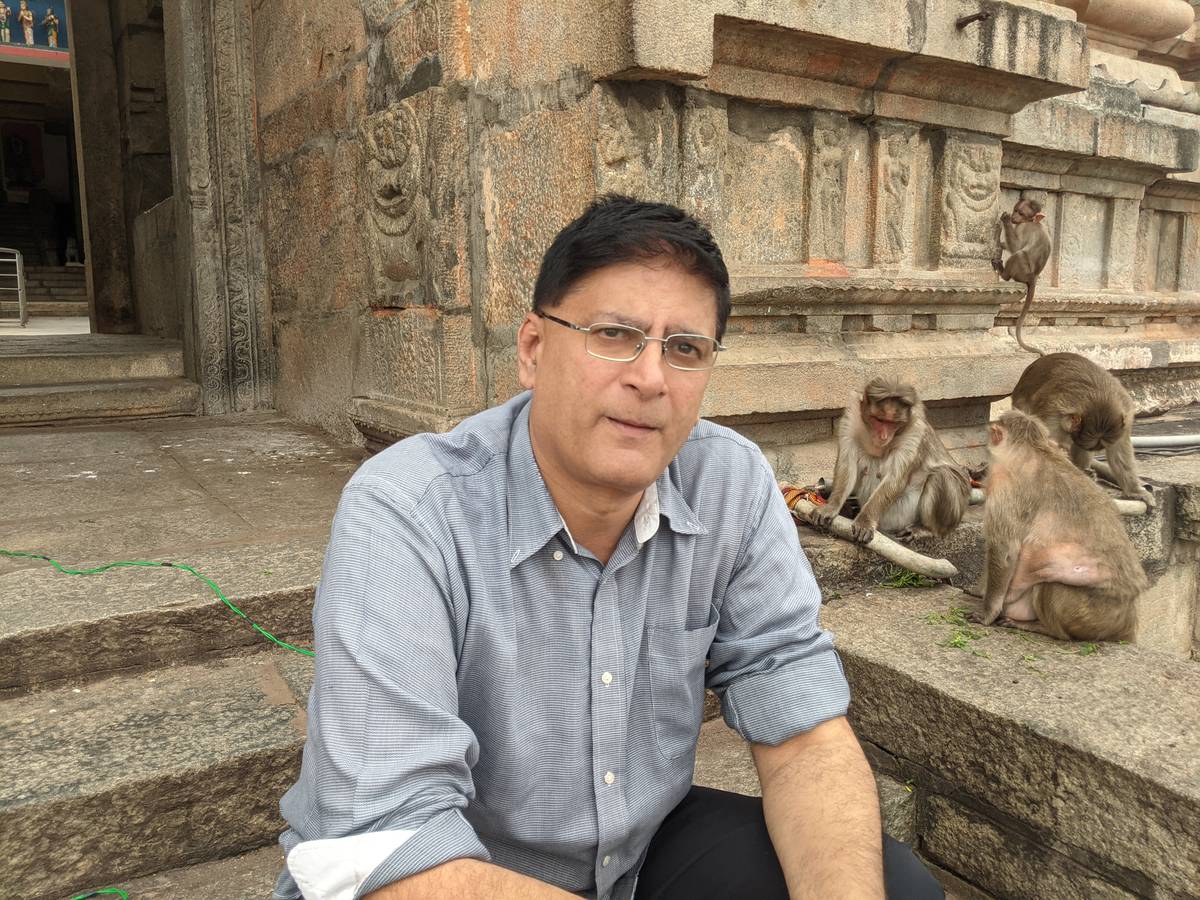

A well-built, upright gentleman runs the store. His deportment is important to the story. He used to be a policeman in the Air Force. He has served in Jaffna, Leh and a host of “interesting” places. I would say he is arresting but that would be unpardonable.

SV Ramachandran, who owns Qurio City, has a passion for collectibles. Antiques, lobby cards, antique furniture, old typewriters, silver minted coins. The small store is large at heart. An antique chest—“It’s more than 100 years old”, he said—takes its place without ceremony among a rash of smaller pieces of furniture that have either been restored or built from antique wood, sourced from the doors and wooden window frames of demolished colonial buildings.

“I have more than 82 varieties of items,” Ramachandran told me. “And I restore antiques in addition. I can restore anything except broken hearts!” he exclaimed, reaching into his inner Quick Fix.

His passion started young. Ramachandran used to accompany his Dad—whom he lost when he was only 12—to places like junk shops. After he retired from the force, he opened the store near his family home on Kamaraj Road.

Despite the dizzying array of antiques and artefacts that Ramachandran has, in his store and his home, his kids have no interest in the business. They always ask him to shut it down. He will not. He clearly loves the place and the business. Soon, he will expand to a location close by, to another very old building. Ramachandran said that he owns a 5000 sq ft location on Jewellers Street, right in the hood. I did not ask what he plans to do with it. I left him before my questions turned cliched.

Jewellers Street is one of the many roads in the commercial area of the Bangalore cantonment area. It houses many…take a wild guess.

Commercial Street is the main drag of the area. But “real shoppers” know that the action is all around it. The commercial district that is a part of Shivajinagar is very loosely bordered by St John’s Church Road in the north, Kamaraj Road on the East, Dispensary Road in the south, and Seppings Road in the west. Seppings spills into the heart of Shivajinagar—the ever-interesting Russel Market. And across the street from it is the imposing St Mary’s Basilica, where the devout worship at a statue of Mary that is dressed in a sari.

Of these streets, Kamaraj Road is an important thoroughfare to the Bangalore East railway station and to the genteel neighbourhoods of Fraser Town, Cox Town and Cooke Town in that order.

A narrow one kilometre stretch of Kamaraj Road is host to a staggering 11 temples. Hindu festival days call for a lot of give-and-take for traffic to move an inch. Also, a Sufi dargah—the Hazrat Ghareeb Shah Wali Dargah and community centres of others, if not places of worship, such as the Cutchi Memon Jamath.

And it is neither surprising nor serendipitous to suddenly see a beautifully renovated building built in 1928, that houses the Veloo Mudaliar dispensary.

The perimeter of this commercial district is about 3.5 km. Its area of about 600 sq m, is a higgledy-piggledy claustrophobia of streets and lanes and by-lanes.

For over a century—maybe more than two centuries considering the MEG is over 200 years old—merchants and bankers have set up shop and home here, catering principally to the employees of the East India Company, and the officers of the cantonment. There were—and are—people from many communities who live in complete harmony and interdependence. Gomti Chettys, Bohra and other Marwaris, Cutchi Memons, Mudaliars and Jews and other denominations of Christians, Muslims and Hindus, not from communities known traditionally to be traders.

There cannot be an urban legend of Bangalore without provoking the ghost of Churchill. One story has it that Simbhu Vilas built in 1924 was where Winston Churchill, as a broke subaltern (junior officer), pawned his wrist watch to a banker, Chaganmull Mutha.

But the writer may have been in a rush to lay claim to an unreported piece of Churchill trivia.

Churchill lived only for about 19 months in Bangalore and that too in the late 1800, around 1896. He hated the quiet of the place, and buried himself in books.

By 1924, Winston Churchill had quit the army and was a Member of Parliament in London and not mucking about in Shivajinagar.

The other problem with this story is that wristwatches were a relatively new thing during Churchill’s time in Bangalore. It was only in 1880 that an officer of the German Imperial Navy suggested to the Swiss horologist, Girard-Perregaux, that a pocket watch strapped to his wrist would be more convenient during combat. It wasn’t until the 1920s that wristwatches were a thing.

But romance overshadows reality. And obviates research.

I peered into every side street and into every old building on Kamaraj. Several old lime mortar buildings exist. With a doorway here, a window there and a weed-covered wrought iron gate that have all seen history.

Age and messy cobwebs of internet and television cables have not diminished their grace.

And neither has age dimmed the grace of the old man whom I encountered again towards the top of Kamaraj Road. He was enjoying a cigarette with his mates, sitting in a doorway, next to a machining shop.

“Hello sir!” he yelled, “did you ask him?”

Ask whom? About what?

“The curio shop owner. Did you ask him about the antique chair?”

I had forgotten all about the sexy silver chair.

“Yes,” I lied, “he said you may take it. It’s yours now!”

The old man clearly understood sarcasm. He slapped his thigh and laughed uproariously. He raised a thumb to acknowledge that I beat him in the banter.

That’s the other thing about old Bangalore—banter.

Image Gallery