The Brave Romance Of Lydia Muttulakshmi Of Fraser Town

Muttulakshmi was not asleep. She slipped out of bed quietly, taking care not to wake her siblings. She could confide in no one. She softly slipped the latch on the door that led to the garden on the side of the house, probably at the back and tiptoed out of the gate. And thus, Muttulakshmi Naidu left home, leaving her past behind her.

Aug 29, 2022, 17 12 | Updated: Aug 30, 2022, 15 30

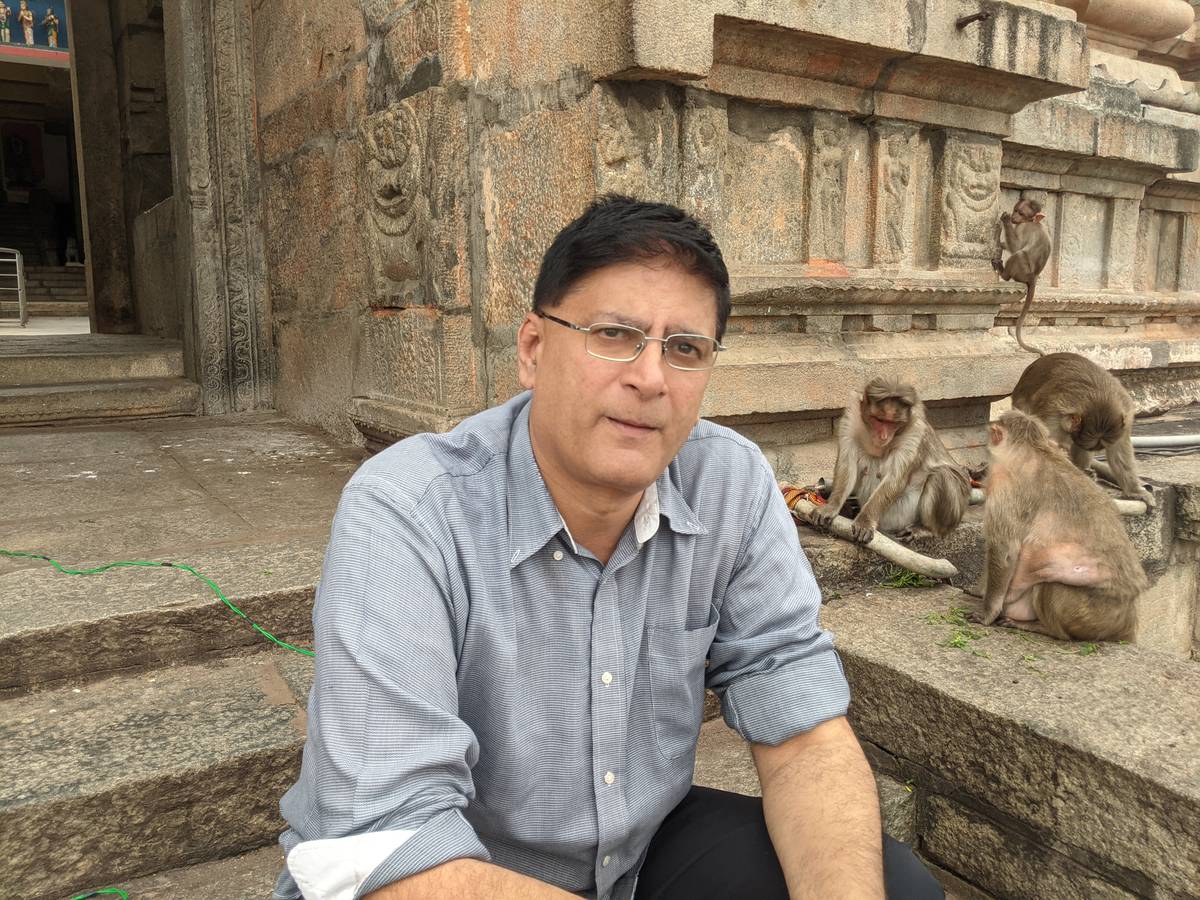

“Architecture or history?” the coconut water vendor asked.

He struck an elegant pose next to the bicycle, which served as his mobile coconut shop.

And just like that, I was back in old Bangalore.

Where—in the 80s—I met a motorcycle cop on Infantry Road, who knew that Bertold Brecht wrote “The Rise And Fall Of Arturo Ui”. He said he was an Eng Litt major in college.

Where—in the 1970s—I used to patronise a small burger shack off MG Road, whose owner—who looked exactly like Pop Tate from the Archie comics—was reading Kafka’s Metamorphosis. (The cockroach on the book’s cover was disconcerting. I was not about to pay for a Kafka burger.)

And in the 60s, there was this lapsed school teacher who could recite all of Shakespeare’s plays from memory. The thing is that he was not an English teacher. He was the PT master.

If the standard association with good education is an upwardly mobile life, Bangalore, at times surprises you with a schooled serendipity from unlikely people. Such as this intellectually curious purveyor of coconut water.

Architecture or history?

I was taken aback. “What? What do you mean?”

“The church. Sir, you are here to see the church, right?”

“Yes, I am,” I replied, “I am not an architect. So, history, I suppose. I am a writer… er… journalist.”

I had been standing on the corner of Promenade and Saunders, across the street from Wesley English Church, admiring it.

It was near the entrance to Coles Park. Near the gate was the usual clutch of loungers, flaneurs, and vendors who sold various edibles. Not to the loungers and flaneurs. They had no money and bought nothing.

The coconut water vendor pointed with his scythe at the Goodwill Girls school, located in the same compound as the church.

“That school is very, very old,” he told me, “over 150 years old. Much history you will find there. More than the church.”

I sort of knew that much, but you cannot really separate the history of Goodwill school from the Wesleyan Church.

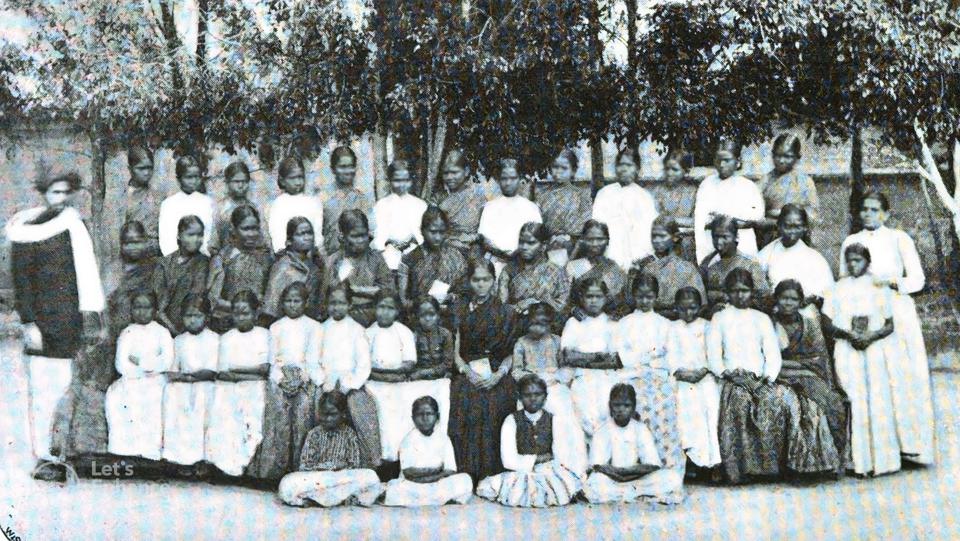

The Goodwill Girls school—originally the Wesleyan Mission School—was founded in 1851, first on MG Road where the East Parade Church now stands. The school moved to its present location on Promenade Road in 1888.

In the same year, 1888, the Wesley English Church was built.

The Wesleyan Mission had purchased the land bordered by Promenade, Saunders, Haines and Spencer roads. And on this property they built the school, the church and the girl’s hostel.

The school, the girl’s hostel and the church all played a part in the story of Lydia Muttulakshmi. Here—some 133 years ago—a young Bangalore girl decided that she needed to break free from the shackles of the society that bound her to a wretched life.

Muttulakshmi was born into a middle class Naidu family. Her father worked as a coach builder. I am not sure what type of coaches. Probably horse drawn buggies.

Per the traditions of the day, Muttulakshmi had been married to someone whom she had never met, when she was only 10 years old. Like many such child marriages, it went nowhere. She was abandoned—or never “claimed” when she had come of age—by the groom’s family, and so she remained in her father’s house.

Tradition has been cruel to women, such as in Muttulakshmi’s case.

First, because she was married but abandoned, she was treated as a widow. A widow was considered a bad omen. They were made to behave like the living dead. They could only wear simple—usually white—clothes and never celebrate anything. They could not attend family or public events.

And second, in many traditional households, women were sequestered in “zenanas”—areas in the back of the house near the kitchen, where men were not allowed.

Being sequestered also meant a number of terrible things including lack of access to meaningful hygiene, medical care and not the least, education. This was not only a hindu thing; apparently the sequestering was true of several Indian christian homes too.

The Wesleyan Mission—like many christian missions whose stated mission was to spread the faith—started to get active in bringing help to communities.

The Wesleyan Mission School—later, Goodwill Girls School—was one example.

Originally, the school was started to educate the children of the Tamil-speaking sepoys serving in the British East India Company’s forces. The curriculum was taught in Tamil and girls were particularly encouraged to get educated. (Goodwill Girls has grown in stature and scope and continues in the present day.)

The mission also employed “zenana” women.

These were ladies who went into homes and brought to the sequestered women what they lacked. The Wesleyan Mission trained them and gave them the professional skills they needed to help their wards, physically and intellectually.

It worked well. The men of several traditional households welcomed the zenana women. They found this to be a solution to the problem of how to free their own women without offending their social- and community circles.

In the suburb of what would come to be called Fraser Town, the church, the school, Coles Park and the people living in the area in the late 1880s, all enjoyed the quiet of the streets.

In one house near the school, lived the Naidu family. Muttulakshmi—an extremely bright girl in her late teens—lived in an independent house with her father, her step-mother, who was her late mother’s sister and her siblings—a sister and a brother.

Muttulakshmi’s father—progressive for his time, we might say—invited and welcomed the zenana women into the home. By available accounts, he did what he could to make the home a happy place for his family. Sending word for the zenana women to make regular visits to his home, was one such effort.

But happiness is not something reserved for the head of a household to dispense.

The world outside for a young, curious, teenage girl was a draw. Muttulakshmi and her siblings looked forward to the visits of the zenana women and their tales of this world that existed outside the zenana.

And then, because their house was said to be right next to the mission school, they would peer over the wall and look at the teachers and the children coming in and out, and listen to the faint sounds of lessons from the classrooms.

Muttulakshmi wanted the freedom to explore a life outside the zenana. But there was no social sanction for her dreams.

By the dictum of her society, she was doomed to live the ignominious life of a widow until she died. She would not be allowed to remarry. It was all simply put down to bad luck and fate, most likely ordained by one’s misdeeds in a previous life and therefore obliged to repeat human existence—like Groundhog Day, but without the memory.

Muttulakshmi was having none of this.

She saw the church as the society that would accept her without judgement about her marital status. And she decided to do something about it. That was to escape to another life.

I narrowed down the day of her freedom to a particular day—13 June 1889.

Establishing this took a little doing.

Although the stories of Muttulakshmi do not clearly mention the year, they do mention that it was 11pm on a Thursday night and that it was a full moon night.

So the question was this: on which Thursdays, in which months, in which years was there a full moon over Bangalore at 11pm?

It was simply a matter of consulting all the moon calendars in the years from 1886 through 1889 to find out. I picked this period because the story was published in England in 1892. Going by my knowledge of the process of publishing—typesetting and printing and editing manuscripts—and by the smell of recent events in the enthusiastic and babbling foreword, the incident could not have happened more than a few years before.

Before long, the likely date that emerged was Thursday, 13 June 1889.

I might be wrong but not materially. So I’m sticking to it.

I told the coconut vendor that I wanted to go around the block and I walked on the streets around the church—Promenade, Saunders, Haines and Spencer. I wanted to see if there was any lasting clue to where the Naidus had lived.

It was pointless, of course. Most—if not all—the old houses are gone. What was I expecting anyway? To find a convenient signboard from 133 years ago that read, “Naidu, Coach Builder”? Then, climb the gate and go sniffing around the zenana in this permissive age?

But I knew I was close enough. Since the stories mentioned the school compound, the house was probably on a section of Spencer or Saunders.

At 11pm on Thursday, 13 June 1889, lamps had long been extinguished and everyone was asleep, probably by 9pm.

This was before electricity. It would be several years before the power from General Electric’s hydel plant in Shivasamudram would find its way to Bangalore.

So, 11pm would have been the dead of night.

But Muttulakshmi was not asleep.

She slipped out of bed quietly, taking care not to wake her siblings. She could confide in no one. She softly slipped the latch on the door that led to the garden on the side of the house, probably at the back and tiptoed out of the gate.

And thus, Muttulakshmi Naidu left home, leaving her past behind her.

She made her way to the Wesley Church. The serene structure looked even prettier in the full moon. At the church were two people—a missionary and his friend, a lady who was a zenana worker. They were still up talking, “having found topics of such interest that they could not sleep”.

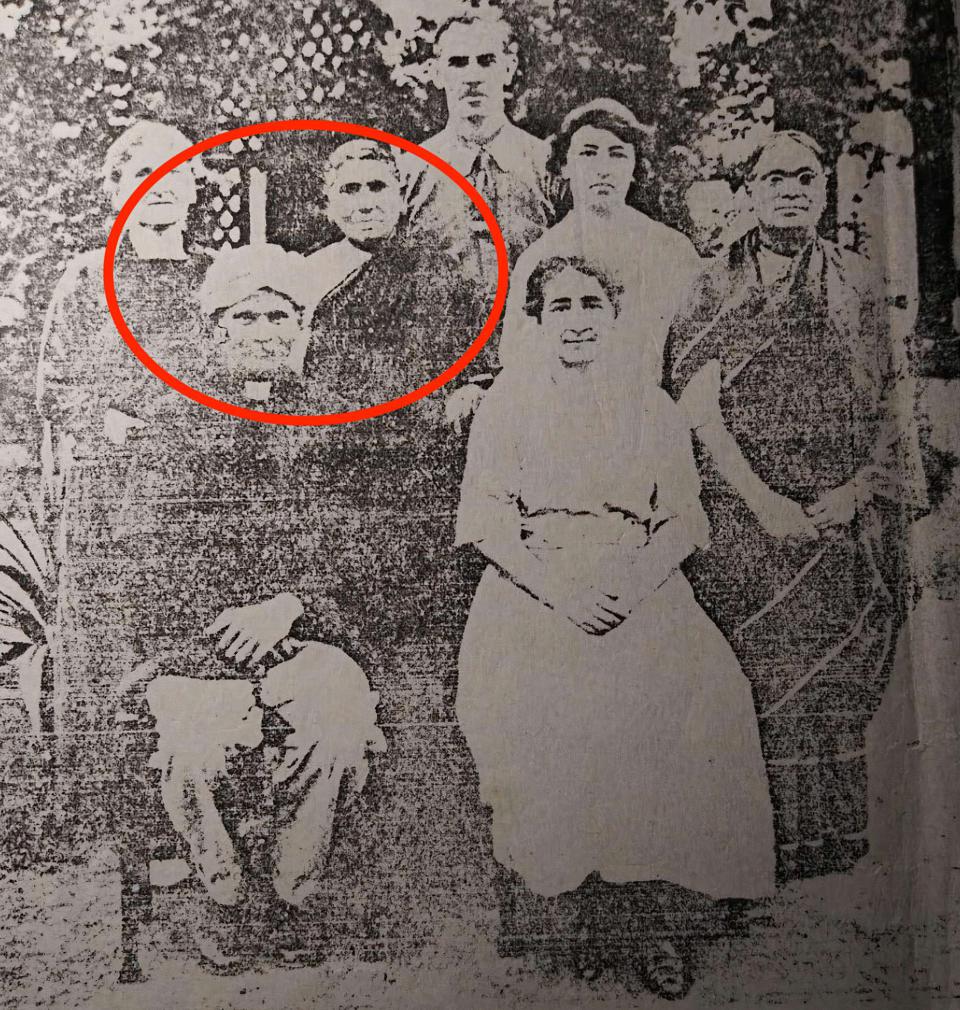

By a description of a Rev Picken,

“Suddenly, with scarcely the sound of a footfall, a tall young woman, dressed in the light, graceful costume worn by Hindu ladies, presented herself in the verandah opposite the door. The missionary rose at once to meet her, and as he did so, she instinctively drew her muslin cloth half over her face, and waited, with averted eyes, for him to address her. To his questions, ' Who are you ? ' and, 'Why do you come here?' she replied, with alacrity and distinctness, 'I am Muttulakshmi, and I come for God.'”

While Picken made it sound like Muttulakshmi’s visit came as a surprise, it is more than likely that the missionary had been expecting her. Picken’s nonsense of “they were up in the church premises, talking till 11pm, absorbed in matters of great interest” would have been unlikely for the age.

For one, the missionary’s friend was a zenana worker and she often visited Muttulakshmi’s home and became Muttulakshmi’s confidant.

And then, there was the time that Muttulakshmi had told her father that she liked the “message” the zenana lady was talking about. Alarmed, the father stopped all the zenana visits and it took a whole lot of coaxing and pleading with him to get them back into the house.

It might not be completely absurd to think that the father may have been distracted at work and forgot to bung in a clip in one of the coach wheels, causing it to come loose and commute independently of the coach. And probably maiming a curious coconut vendor.

The point was that Muttulakshmi wanted out. And this young girl walked down what must have been completely deserted streets that were unlit and probably ghoulish in the moonlight, to get to the mission. She spent the night in the girl’s hostel, and awaited the next day.

The scatologically-adjacent noun hit the manually-operated punkah.

The upper caste Hindus of Fraser Town and the general Ulsoor area threw a hissy fit. They corralled support from the public and tried to storm the church and get Muttulakshmi to go back home to her zenana. But Muttulakshmi—who now called herself Lydia Muttulakshmi—was determined to chart the course of her own life.

In the Biblical meaning, Lydia means beautiful. And Muttulakshmi is a shout out to the Hindu goddess of wealth, Lakshmi. But that is not a title—like Chancellor of a Divine Exchequer, such as the Hindu of Westminster, Rishi Whatsis—but to whom one prays to get more money. Ok, exactly like Rishi.

The months succeeding Lydia Muttulakshmi’s defection were a test of wills and ego. Lydia Muttulakshmi’s father was a pawn in a vocal and very public opposition from people who were very upset by all this.

Lydia herself was no pawn. She wanted no part of this controversy and merely wanted to be left the heck alone.

There were hard choices for both sides.

All in the name of god.

The upcaste Hindu people said that they did not like this “rapidly developing department of missionary activity”, which they saw as “Christian aggressiveness”. They did not want to remain silent, even if it meant disrespecting an individual’s choice.

The mission did not want to baptise Muttulakshmi right away, because they felt that rushing to baptise one person might lead to such an opposition that Hindus might deny zenana women entry into their homes and further pull their children out of mission schools, causing the larger agenda of spreading the missionary word, to be prejudiced.

But denying Muttulakshmi her request would be contrary to their mission statement. Per Picken,

“...had conviction had been wrought in this Indian girl's heart by the Holy Spirit, the refusing of her request might be the beginning of a struggle against God.”

So they quickly went and baptised her.

Striking a needlessly defensive posture, Picken quoted loftily from Tamil literature.

There were many British Tamil scholars at the time. Fred Goodwill—after whom Goodwill Girls School was named—was one. He authored many books, including one on Shaivism. From translations of their works, many bonhomies could be harvested.

These lines, from the 18th century Tamil and Sanskrit scholar, Tayamanavar, translated by Dr Graul—an otherwise soft spoken man.

Thou standest at the summit of all the glorious earth, | Thou rulest and pervadest the world from ‘ere its birth, | O Thou Supreme Being I And can the pious man find out no way to Thee, | Who, melting into love, with tears approaches Thee, | O Thou Supreme Being?

And this from the Thirukural, composed in 500 AD or thereabouts:

'Though men should injure you, their pain | Should lead you to compassion ; | Do naught but good to them again, | Else look to thy transgression.'

(They used spaces before semicolons before Twitter rationed punctuation.)

The opposition was not backwards in coming forwards.

They hit back with a very public campaign which included this gem, a letter circulated as widely as they could.

Here’s how it read:

To the Hindu inhabitants of Bangalore Cantonment, Shûlé, Alsûr, and other places:

Aryan Brethren,

' Many of you are accustomed to send your children to the mission schools under the care of Christian preachers. Although you know the true reports concerning them, you have not removed your children. So that you may not be deceived by believing those false persons, I will briefly relate what has actually occurred. Kindly give attention…’

The letter was coyly signed, “A Hindu Religionist”.

Some newspaper headlines were supportive of the “aryan brethren”.

“Mission Schools To Let”; |

“The Conversion Agitation” ; | and

“The Anti-Missionary Meeting”

People reacted to this campaign, and for a while, parents yanked their kids from mission, or “convent” schools in protest. But that did not last long.

There was an effort by some lawyers to drag Lydia Muttulakshmi to civil courts and panchayats, only to be told that her decision was by adult choice and that no one had the right to decide where she would live.

Lydia Muttulakshmi was stoic and uncaring through all this. She met her siblings from time to time and sent word to her father, who was woke.

The father’s love of his daughter prevailed. He shook off the protestors and came to terms with the new scheme of things and supported Lydia Muttulakshmi.

Anyway, it all became very boring. The public interest waned. The lawyers’ fees waxed. And the noise died down.

Briefly though, the noise went up again, because love had inevitably crept into the story.

In the course of her missionary positions, Lydia Muttulakshmi met her young and handsome prince in a preacher, Asirvatham Paramanandam. He was from the Tamil Wesley Church. That church used to be a part of the Wesley Mission, but was moved further down Haines Road, to its present location, just past Bamboo Bazaar. It’s another beautiful building with the same recognisable architecture.

In the time after Picken’s narrative, Lydia Muttulakshmi married Rev Paramanandam.

While so, it is likely that it connects to the sorry tale of how the ex-husband reappeared into her story.

Probably because Lydia Muttulakshmi was technically married, she would need a divorce or annulment for her to move on. So efforts were made to find the husband.

It took the better part of two years.

But no sooner had they found him, he hit them up for money. He demanded legal compensation of 40 pounds—a large amount at the time. He made the case that because his “wife” had converted, he needed to remarry and hence needed money. The mission pondered this and decided he had a point. They haggled with him for a bit and he settled for 30 pounds.

The mission rallied around the girl and raised the money via a personal loan, and then formed committees to pay it back. And thus, she was relieved of her albatross.

There must have been a good reason for everyone to make such an effort and crowdsource money for her divorce. And usually, the only cause for the urgency to get a divorce is to be able to remarry.

So—without the need for much astute deduction—it is easy to conclude that Lydia Muttulakshmi had met Asirvatham Paramanandam and the two had fallen in love and therefore needed her divorce.

In their time together, the couple were active in the flock. They used their house on Sunderamurthy Road (which is off Assaye Road) to host congregations. And when that got too crowded, they bought the Magnum Talkies (or Theatre) in 1924 and converted it into the St Peter’s Church on Gover Road, which is right off where they sell kebabs on MM Road in Fraser Town.

They probably lived happily ever after on Sunderamurthy Road in a relationship that lasted until the time that this brave, defiant Fraser Town girl and her new husband were buried in their graves in the Indian Christian Cemetery in Hosur.