The Burden Of Vikram’s Song

This diverse experience is something that ought to snuggle up and spoon nicely with BIC’s credo. But no job is without its challenges, so we tried to find out what monsters lurk under Vikram Bhat’s bed.

Apr 23, 2024, 11 46 | Updated: Apr 23, 2024, 21 48

Standing just outside the hub of Indiranagar, but right in its buzz, is the Bangalore International Centre.

For members and regulars, BIC is a lifeline to everything intellectual—a connection they can feel, without it being subject to the apology of commercial considerations. A place of refuge for the intellect—for them and the casual visitor, and deservedly, everyone else in Bangalore.

From the day of its inception, and seemingly without skipping a beat, BIC has settled into its role of primacy as a beacon of culture in the city.

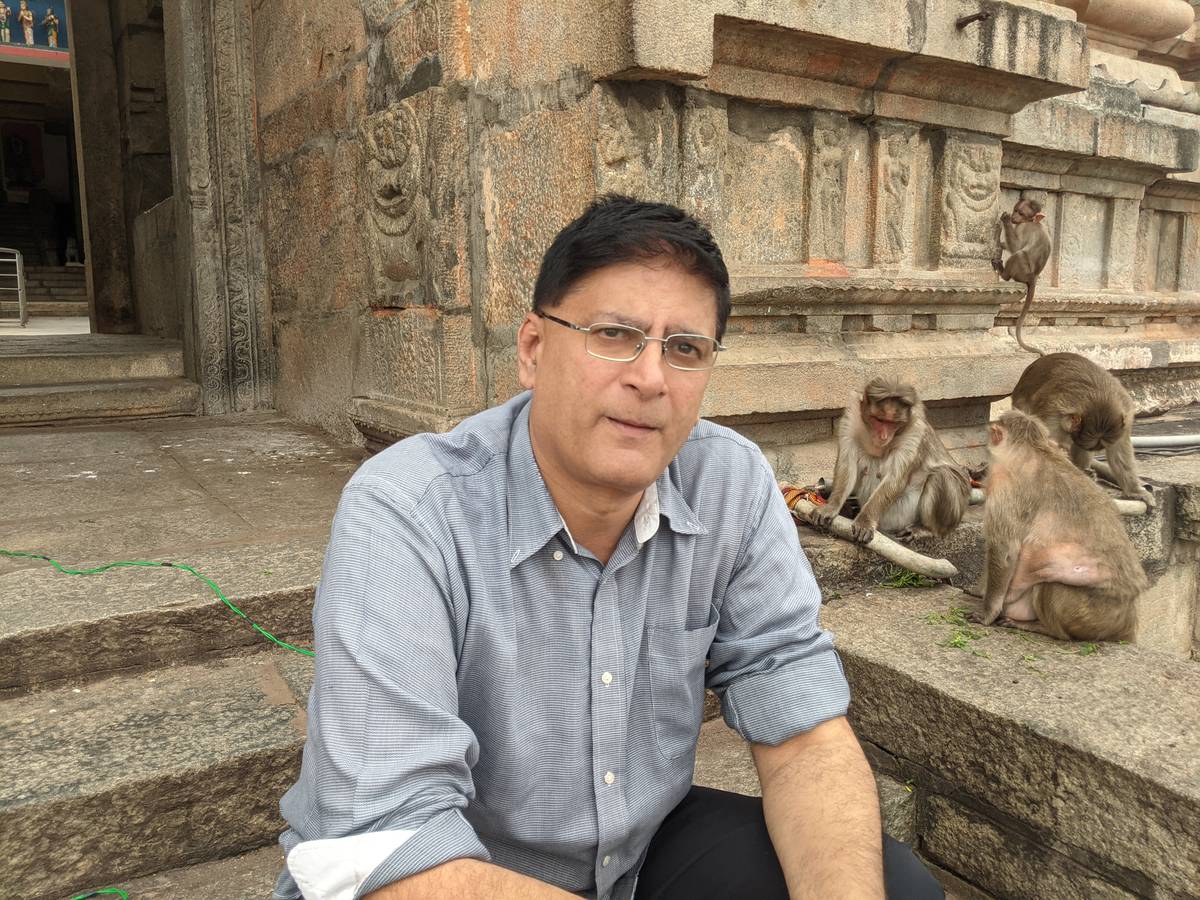

And after years of being shepherded and deftly bullied into a spirit of inclusiveness—an all-embracing cultural ethic successfully hammered into its DNA by former director V Ravichandar—BIC gets a new director, Vikram Bhat.

Bhat has an interesting and eclectic background.

Based many years in New York City, he has been a techie; he has been a stockbroker, and then, after he returned to India, he graduated from an Edu course so he could teach, and he has worked as a teacher. And now, he is the Director of the city’s premier cultural institution.

This diverse experience is something that ought to snuggle up and spoon nicely with BIC’s credo. But no job is without its challenges, so we tried to find out what monsters lurk under Bhat’s bed.

Bangalore International Centre is an extremely popular venue, their events are top-class and, importantly, free. (We speak of BIC events, of course, not those by private organisations who have booked the auditorium or one of the halls for their own event.)

BIC events—curated by a committee of (culturally-astute) members—are frequently full house.

The Centre looks beautiful and rocks the style and sweep of cultural institutions of note anywhere in the world. (And the obligatory pre-event coffee isn’t too bad either.)

Bhat takes pains to say that these privileges have been handed to him.

Among the things that are not on Bhat’s worry-list, is money—the bane of most cultural organisations.

Any society with a thriving cultural milieu is a patron of its talent. Which means they donate generously and that was happy tidings in the early days of the BIC. Bhat said that today, the BIC model is financially sustainable and he would not worry too much about the finances.

The mission that hangs above his door (metaphorically, of course) is to make BIC even more cultural.

BIC has achieved a premier status within Bangalore, but that isn’t enough. Bhat’s pursuit is to make Bangalore a cultural stop in a more global arena.

He explained that larger cities like Bombay and Delhi seem to be the natural choice for most artists who travel to India. Music, dance, or theatre will choose these cities when planning an India tour. Bhat wants Bangalore on that list.

For example, “Pixel”, a French, dance-and-tech melding experiment, played in Delhi, but not in Bangalore, Bhat said, vexed.

One way, that he believes, he can increase the scope and scale of presenting Bangalore as a venue of choice is through partnerships. To that end, he is working towards collaborating with other cultural spaces in Bangalore, like Indian Music Experience, Museum of Art and Photography, Science Gallery, and Bangalore Creative Circus.

At the BIC, Bhat would like to increase their offering. “My goal is one good event a day. We are at 400 events, to make it 500 I have to make the process more transparent.”

Of banes and challenges, Bangalore’s off-putting traffic is another culture-thwarting reality.

Going to a great event, even if it happens a reasonable distance from one, takes motivation and willpower. But a good event in one's own hood makes culture accessible. The partnership among venues and institutions could, for instance, lead to a multi-venue ticket. “London and New York have things like a five-venue pass that you can buy at the airport. Why can’t Bangalore have that too?” Bhat pointed out.

The next on his to-do list is to increase BIC’s appeal to a younger audience. He needs to figure out how to attract people under 40. He explained that younger audiences clearly do not like formulaic content. The present format at the BIC—panel discussions followed by a Q&A—doesn’t seem to resonate with younger Bangaloreans.

Some of the topics that engage a younger intellect are different from those in higher age groups. For example, gender, caste and sexuality—Bhat said there is a lot of angst young people have about these.

Bhat explained, “It is a massive mental health time bomb we are sitting on. Art spaces have a big role to play in that. Caste is like race in America. They find a way of coming back into the world. It’s about having a respectful conversation around it.”

Bhat feels that BIC’s podcast should help hit the younger demographic. BICs ideal audience is someone who is curious.

The good thing is that the BIC team is young. (Hiring the young with promise was something that V Ravichandar acted upon. Speaking to Explocity Ravichandar said, “I like [their] energy and ideas.” He said he vested in them and encouraged failure—“If we fail, let’s fail together and fail fast”.)

Next on the list is local culture—Bhat believes that a Bangalore cultural institution should create a space that includes Kannada culture as part of the mainstream.

But can it? And why hasn’t it, yet?

Explocity put this question to one of Bangalore’s best-known cultural icons, Prakash Belawadi—writer, journalist and theatre and film personality.

Belawadi believes that forcing a Kannada agenda in culturally- and ethnically-diverse Domlur is “tough”.

“Anyway, it’s the job of the Kannada Development Authority to use taxpayer money to promote the culture. They should promote films and literature,” he said, “Bangalore speaks many languages and we should promote that.”

Belwadi’s belief in cultural- and editorial independence slewed politically. Commenting on BIC programming in general he said, “I’ve always felt the programming has become a little left-liberal. But I don’t feel resentful about that. The personality of the curator should be allowed to come through, A city should allow for that kind of expression.”

From one angle, Bhat is the prototype of a “young CEO” and he said his ops-heavy job is similar to that of a General Manager of a five-star hotel.

We asked him what he wakes up to every day. What does getting to work mean?

“It’s a steep learning curve. I view it as a privilege. It's a chosen challenge to wake up to every day.”

Image credits: Lekha Naidu