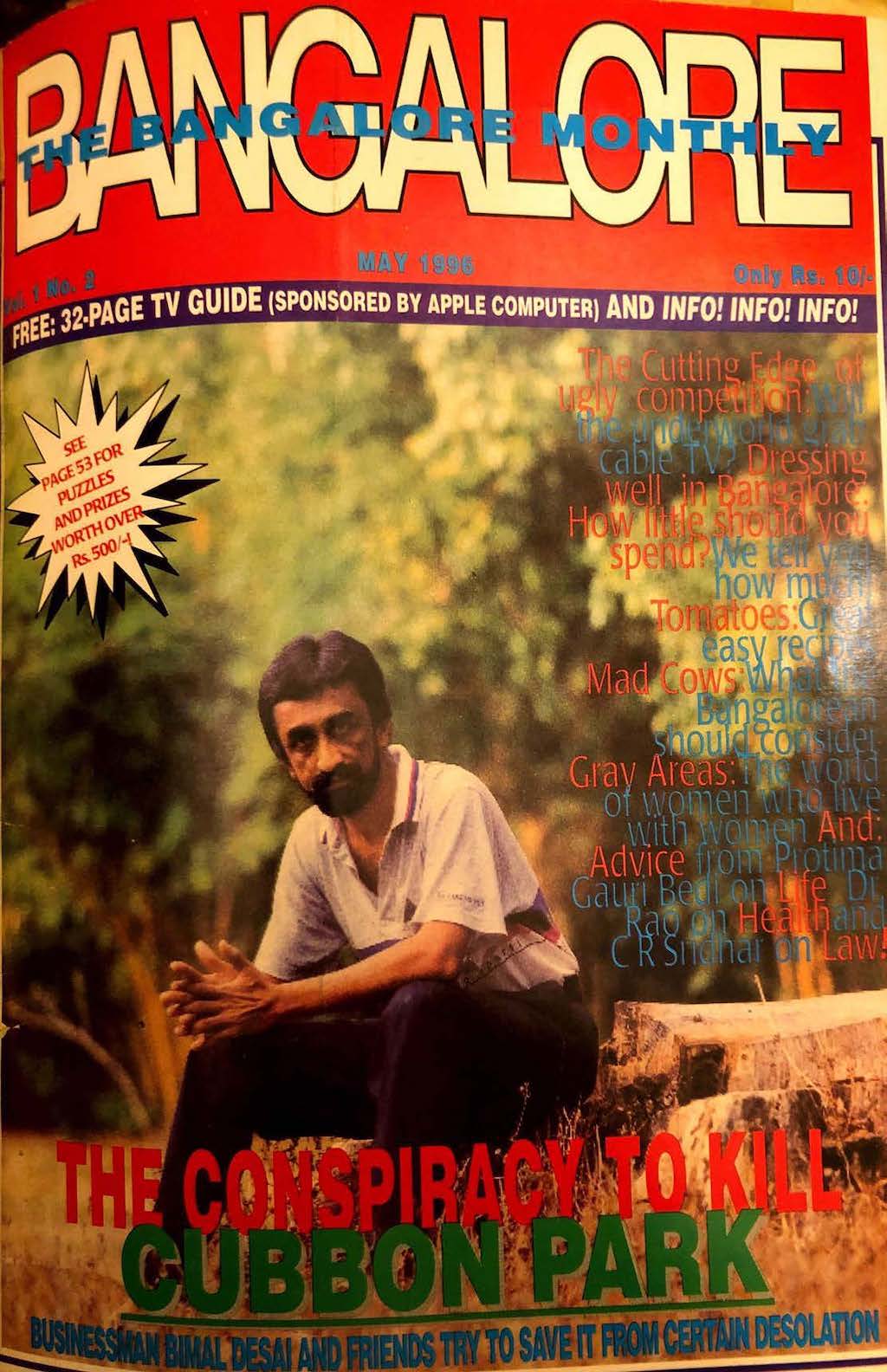

The Conspiracy To Kill Cubbon Park

How a concerned citizen, an environmentalist and a judicial activist saved Cubbon Park

Feb 20, 2021, 02 26 | Updated: Feb 22, 2021, 18 50

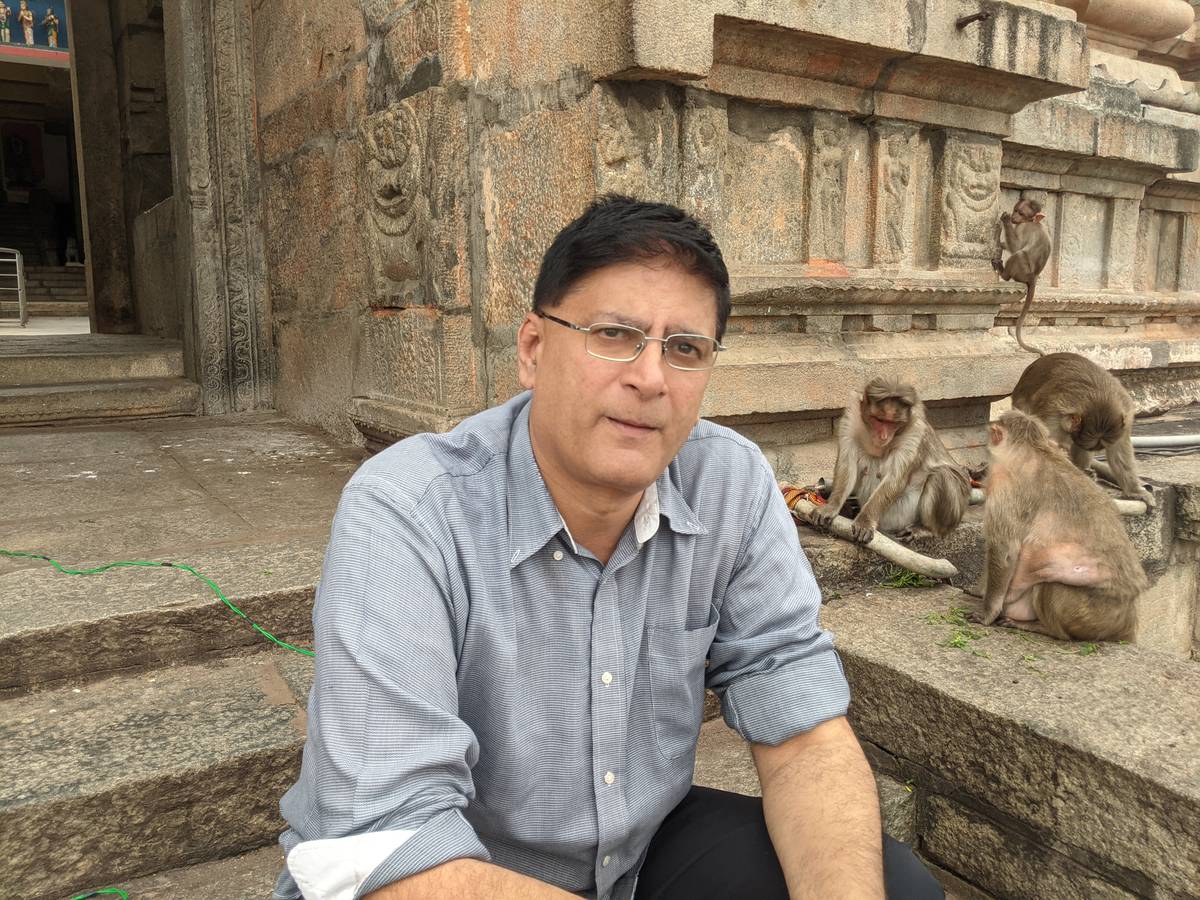

At 6:30 am every morning for several years, Bimal Desai, Bangalorean businessman and amateur stage actor. would park his car near the Press Club, walk across to the area behind the HIgh Court and begin his constitutional run.

Starting from the pond near the High Court steps that led to the bandstand, he would trot out past the Queen’s statue, past Bal Bhavan, towards the part of the park near the UB HQ; follow the park’s natural outer periphery down Kasturba Road, re-enter the park near the Venkatappa Art Gallery, run around the moat, around the bamboo groves nearby, then break into a gallop on the grassy straight that leads back to the High Court.

These geographical points of reference, the ponds, the moats, the bamboo groves and even the grassy straight, are very nearly things of the past.

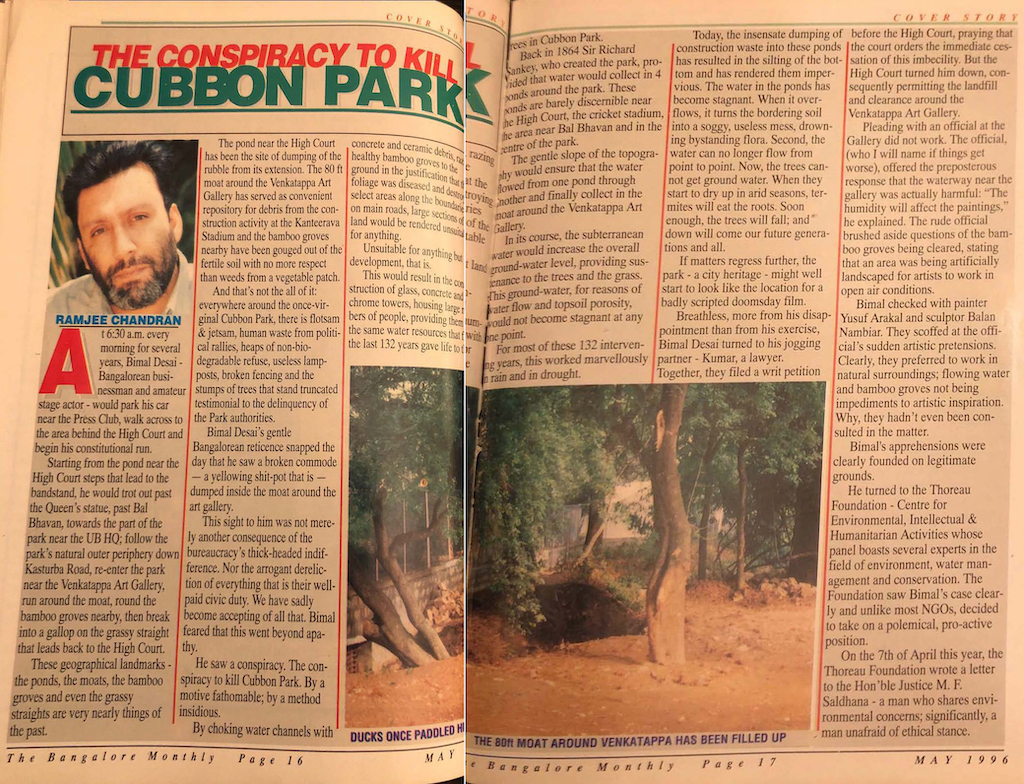

The pond near the HIgh Court has been the site of dumping of the rubble from its extension. The 80 ft moat around the Venkatappa Art Gallery has served as convenient repository for debris for the construction activity at the Kanteerava Stadium and the bamboo groves nearby have been gouged out of the fertile soil with no more respect than weeds from a vegetable patch.

And that’s not all of it: everywhere around the once-virginal-Cubbon Park, there is flotsam and jetsam, human waste from political rallies, heaps of non-bio-degradable refuse, useless lamp posts, broken fencing and the stumps of trees that stand as truncated testimonial to the delinquency of the Park authorities.

Bimal Desai’s gentle Bangalorean reticence snapped the day he saw a broken commode - yellowing shit pot that is - dumped inside the moat around the art gallery.

This sight to him was not merely another consequence of the bureaucracy’s thick-headed indifference. Nor the arrogant dereliction of everything that is their well-paid civic duty. We have sadly become accepting of all that. Bimal felt that this went beyond apathy.

He saw a conspiracy. The conspiracy to kill Cubbon Park -- by fathomable motive, and insidious method.

By choking water channels with concrete and ceramic debris, razing healthy bamboo groves to the ground -- with the claim that the foliage was diseased and destroying selected areas along the boundaries on main roads -- large sections of land would be rendered unsuitable for anything.

Unsuitable for anything but development, that is.

This would result in the construction of glass, concrete and chrome towers, housing large numbers of people, providing them with the same water resources that for the last 132 years gave life to the trees in Cubbon Park.

Back in 1864, Sir Richard Sankey, who created Cubbon Park, provided that water would collect in four ponds around the park. These ponds are barely discernible near the High Court, the cricket stadium, the area near Bal Bhavan, and in the centre of the park.

The gentle slope of the topography would ensure that the water flowed from one pond through another and finally collect in the moat around the Venkatappa Art Gallery.

In its course, the subterranean water would increase the overall ground-water level, providing sustenance to the trees and the grass. This ground-water, for reasons of water flow and topsoil porosity, would not become stagnant at any one point.

For most of these 132 inventing years, this worked marvellously in rain and in drought.

Today the insensate dumping of construction waste into these ponds has resulted in the silting of the bottom and rendered them impervious. The water in the ponds has become stagnant. When it overflows it turns the bordering soil into a soggy, useless mess, drowning bystanding flora. Second, the water can no longer flow from point to point. Now, the trees cannot get ground water. When they start to dry up in the arid seasons, termites will eat the roots. Soon enough the trees will fall; and down will come our future generations and all.

If matters regress further, the park - a city heritage - might well start to look like the location for a badly scripted doomsday film.

Breathless, more from his disappointment than from his exercise, Bimal Desai turned to his jogging partner Kumar, a lawyer. Together, they filed a writ petition before the High Court praying that the court orders the immediate cessation of this imbecility. But the High Court turned him down, consequently permitting the landfill and clearance around the Venkatappa Art Gallery.

Pleading with an official at the Gallery did not work. The official (whom I will name if things get worse), offered the preposterous response that the waterway near the gallery was actually harmful: “The humidity will affect the paintings,” he explained. The rude official brushed aside questions of the bamboo groves being cleared, stating that an area was being artificially landscaped for artists to work in open air conditions.

Bimal checked with painter Yusuf Arakal and the sculptor Balan Nambiar. They scoffed at the official’s sudden artistic pretensions. Clearly, they preferred to work in natural surroundings; flowing water and bamboo groves not being impediments to artistic inspiration. Why, they hadn’t even been consulted in the matter.

Bimal’s apprehensions were clearly founded on legitimate grounds. He turned to the Thoreau Foundation - Centre for Environmental, Intellectual and Humanitarian Activities whose panel boasts several experts in the field of environment, water management and conservation. The Foundation saw Bimal’s case clearly and, unlike most NGOs, decided to take on a polemical, pro-active position.

On the 7th of April this year, the Thoreau Foundation wrote a letter to the Hon’ble Justice Michael F Saldhana, a man who shares environmental concerns; and significantly, a man unafraid of ethical stance.

On the evening of 10th of April, Bimal Desai stood, with the trepidation of an expectant father, outside Justice Saldhana’s chamber. In the hour past 9 p.m., Justice Saldhana delivered his 10-page suo moto order.

In one fell swoop, (an ironic term in this context), the judge has banned political rallies in the park, has ordered immediate cessation of the felling of trees, has ordered the restoration of the four ponds and water channels to their original plenitude within 45 days, has enjoined the Century Club (who have applied for permission to hack trees to make way for structures) from cutting trees. And for good measure, he has asked explanation from the Indiranagar Club about the felling of 29 trees on their premises.

What’s more, he has asked the government of Karnataka to explain to him on the 13th of June, what measures the Police have taken to improve the law & order situation in the park.

This ought to have the effect of a gentle rain falling over Cubbon Park after an arid season devoid of environmental concern.

But already, the people interested in the devastation of Cubbon Park have started to look for new routes to get around Justice Saldhana’s order.

Additionally, the Century Club has pressed on for permission to cut down two trees for an extended administrative block. (God knows we have enough administration in this land.). The club claims that it does not fall within Cubbon Park since the land on which it stands was a gift from the Maharaja of Mysore. If this technical quibble is true, will they fall outside the applicability of Justice Saldhana’s order?

The experts say that at the present rate of degradation, they do not give the park more than 15 years of survival, unless Justice Saldhana’s orders are implemented immediately.

Otherwise, the efforts of Desai, S Malini, a tree warden & journalist who has actively embraced the cause, the Thoreau Foundation and importantly, the orders of Judge Saldhana himself, will be dissipated through bureaucratic misinterpretation and venality.

While it is often that we take issue at cocktail parties with the temporary fanaticism of armchair-revolutionaries, very few of us have actually translated our anxiety into action.

But what is most disconcerting is that this threatens to take on the proportions of a war - one that is fought along ego lines rather than on the basis of propriety and concern for what has made Bangalore the most beautiful city in the country.

I asked Bimal Desai how he felt about winning the battle: “Winning? What winning?,” he said wearily, “it has only just begun. Now, we have to clean up Cubbon Park.” Without the active support of us Bangaloreans, that may never yet become a reality.

This article was originally published in The Bangalore Monthly, Issue dateline: May 1996.