The Inscription Hunter—Finding Bangalore’s History With PL Udaya Kumar

Not since BL Rice has anyone attempted to document all the inscriptions found across the city. This time, digitally.

May 04, 2024, 17 48 | Updated: May 07, 2024, 10 16

Sometime in 2017, PL Udaya Kumar—an engineer then employed at Schneider Electric—was home in Rajajinagar. It’s a neighbourhood in which he has lived in all his life, except when he was off studying engineering at the IIT in Madras in 1991.

He received a call and it was someone who said something about finding an old inscription stone. The caller said it might have something to do with Kethamaranahalli—a village that is ancestral to modern Rajajinagar.

Indeed, in the days of early history—right back to the pre-medieval days—the whole of Bangalore was a collection of little hamlets, connected socially and commercially. In time each of these villages or village-clusters grew into the neighbourhoods, the collection of which make up the city of Bangalore.

That’s pretty much how old cities anywhere in the world grow. Take J P Nagar, for instance, which grew around the old settlement of Sarakki. These villages are often inconspicuous and with no effort, soon forgotten. Or, for a more distant example take Heathrow in London. “Heath” in old English means an uncultivated area and “row” is several of those. Once a tiny little village, now the delight of world travellers.

Anyway, Udaya Kumar got the call, and, his interest piqued, he set off to look at this stone.

He walked down the narrow alleys of Kethamaranahalli, asking the village elders if they knew of this stone, and he finally found it. It was a “veeragallu” or hero stone. (Veeragallus honour those who lost their lives in the line of duty—defending the property of the country for instance.

Lying abandoned in a corner, in the middle of rubbish and refuse, was a slab of history—one that revealed to him his hood was more than 700 years old*.

This moment stirred something deep and sentimental within him and the feeling would not go away.

So he started to poke around to find out what this stone was even about and learned that there was a record of thousands of such stones, published in a multi-volume set of books titled Epigraphia Carnatica—compiled by then Director Of Archaeology, Benjamin Lewis Rice.

(Listen to Episode 2 of podcast, The History Of Bangalore, “How We Discovered The History Of Bangalore”.)

And then—donning a metaphorical fedora and whip in hand (we explain this later) Udaya Kumar set out on a mission to hunt down every stone recorded there.

Hearing of his work, the Mythic Society—a fabulous organisation in Bangalore that is devoted to history and heritage—offered to make things official and Udaya Kumar quit his job. And is today, full time on the quest to find inscriptions, use digital imaging techniques to find traces of inscriptions that might be weather-worn and record their contents and make them available to the public, such as on this Google map.

His starting point for all this was Epigraphia Carnatica.

Epigraphia Carnatica is an exhaustive 12-volume book on the inscriptions found in the Mysore kingdom. It was written between 1894 to 1905.

There were supplements and connected gazettes published since but after 1920 or so, there is little reference to them and in recent years, they are all but forgotten. Most modern residents of Bangalore display little to no knowledge of its existence—or for that matter, the existence of the inscriptions, let alone understand their significance to our history.

Along with a few copper plates, these inscription stones are the only record of the history of this land.

Dating back to the 5th century, they present a record of major events as seen by the record keepers of the day. These stones have carved on them, land records, disputes over cattle and property, temple and land grants and other royal edicts and of course, the veeragallus—records of battle, of war and deaths of important people who dies honourably by the definitions of honour of the day.

This all-but-total apathy to our history have led to these stones being ignored, or worse, used for practical reasons, such as drain covers, leg support for benches or very simply cast aside.

That said, there is also the matter of the weird and incomprehensible relationship between the people of an area and the inscriptions in their neighbourhoods.

In many places, local residents accord these stones mystical powers and believe often that there is treasure, such as a pot of gold, buried beneath them, and as such as they are not to be tampered with. Yet, these very stones are ignored on a daily basis and you can find them covered in garbage and lying in ditches, often peed on by different species of mammals including, probably, the human kind.

This was the case with the all-important stone found in Hebbal. Called the “Kittaya stone”, this veeragallu speaks of the death of a Kittaya who died defending his village of Hebbal in an attack by the Rashtrakutas, who used to carry out raids on Ganga dynasty strongholds back in the 8th century.

The local municipality was about to bury the stone in some roadworks, but an alert citizen called a group called the Revival Heritage and they in turn set off a series of actions to save the stone.

Once they overcame the objections of the locals—who preferred that the stone be buried in roadworks, rather than joust with fates and allow it to be removed—epigraphist Dr PV Krishnamurthy reading the stone deciphered what it said. The result, it was the oldest inscription found in the Bangalore region and wrote a little more into what we know of the history of the city.

Udaya Kumar then joined the project to save the stone and applied his techniques to record it.

But he did not stop there. There was the question then of what to do with the stone—that had been placed temporarily in a nearby government-owned facility—and he came upon the idea that they would build a mantapa to house it.

He got architect-historian Yashaswini Sharma to design and build the mantapa. She used techniques that were used during the time of the Ganga dynasty in the 8th century and Udaya Kumar—in the spirit of giving the local populace a sense of ownership of their history—crowd-funded the project.

Today, about 1250 years after it was carved, the Kittaya stone stands in that mantapa, preserved for another era. (https://maps.app.goo.gl/HxSvhybz6Ex8iGGw8).

Peppered across Bangalore, many of these stones have unfortunately been lost to development.

Kumar with his team is recording and chronicling these stones. Today, he is the Honorary Director for the Bengaluru Inscriptions 3-D Digital Conservation Project of Mythic Society.

In the initial days, the project was funded by Kumar himself and he got help from heritage enthusiasts and history buffs. “Most of the early work was done for free. For example, the scanner we use to take high resolution 3D pictures of the stones… the seller was a lover of history, so he said we could borrow it on weekdays. The project was also not that big then, we found just a few stones here and there.”

Today, when they have a database of 1500 stones, the whole project is financed by the Mythic Society, a society founded in 1909 to study and conserve history.

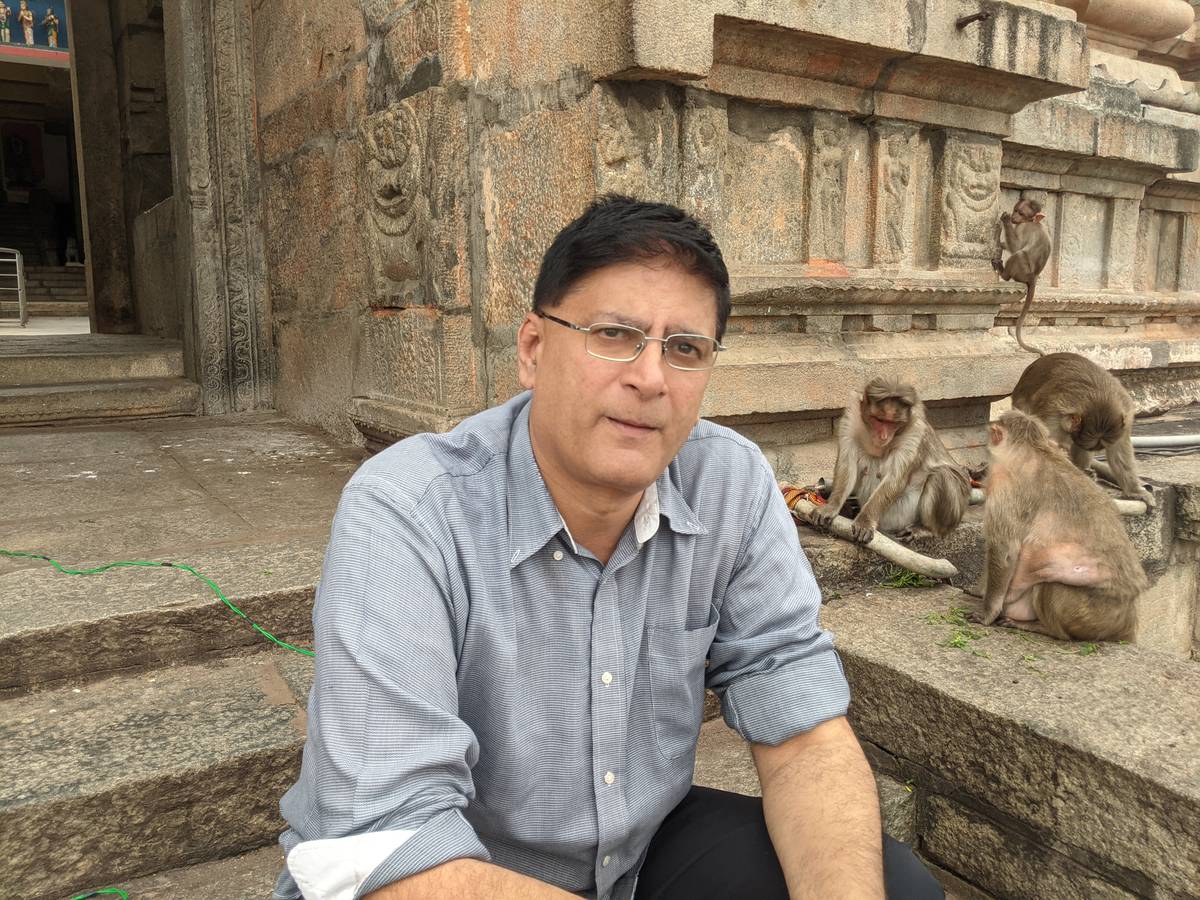

Ramjee Chandran (host of the podcast, The History Of Bangalore” calls Udaya Kumar, Bangalore's inscription hunter.

“I give Uday that label with the admiration I reserve for Indiana Jones,” he said.

Chandran added, “I engage with him frequently. He is doing a great job—and publishes his findings freely so everyone can have access to it. An attitude both unusual and refreshing."

Initially, Kumar started this project while taking a sabbatical from his day job.

“I’m still supposedly on that sabbatical,” he explained, “this project probably needs another two years or so. I’m probably planning to go back to work, but I’ll decide at that time.”

The hands-on historian continues to live in Rajajinagar with his wife and his daughter, who are very supportive and have been part of some of his projects too.

“I was born in Rajajinagar, and I will hopefully die there as well,” he laughed.

Not till he gets all those inscriptions.

You can catch PL Udaya Kumar on the History of Bangalore podcast right here:

*Following the publishing of this piece, Udaya Kumar called to clarify that he had come to realise that the stone at Kethamaranahalli had been destroyed and that the residents of the area had actually led him to another, in his neighbourhood. To T Dasarahalli where he discovered the stone featured in the photograph.