Why I Can’t Stand Bangalore Nostalgia

Unfortunately, almost everyone who writes about Bangalore writes with wistfulness; their reminiscing is gentle humour set in the melancholy of a black and white photo.

Feb 20, 2021, 18 56 | Updated: Feb 20, 2021, 18 56

Nostalgia is a waste of time.

Literally. It wastes the time gone by, which is the past. It defies Einstein.

Unfortunately, almost everyone who writes about Bangalore writes with wistfulness; their reminiscing is gentle humour set in the melancholy of a black and white photo.

Even their happy childhood memories are stained by sepia-tinted parents who were distracted because they had had too many children, an auntie who baked Madeira cake and inevitably, a goofy uncle who did not quite make the cut... a 'what may have been' collection of bittersweet tales—of mild, wholly excusable foibles of the totally loveable relatives of the author.

Many of these books may be nice reads and the dudes who wrote them may be intelligent folks, but there’s too much sickly, syrupy nostalgia about Bangalore.

What we need are books about murder—books titled “Murder On Namma Metro”, or better, “Murder Of The Supermarket Marauders”.

I don’t have a particular supermarket in mind, but Thom’s Café will do nicely.

The people I would like murdered in the book are the shop’s (well-to-do) patrons who push, shove and jostle those who are also trying to pay their bill.

Like the large young woman—the most gentle term I can conjure up to describe her would be “harridan”—who first pushed past me at the checkout counter, shoved me sideways with her ampleness and then looked sharply at me as though I had outraged her XXXL-sized modesty. (Her size mattered because the description of it is necessary to emphasise the heft of her heave. And the consequent propulsion of my credit card as it accelerated out of my fingers and fell through the tiny space between the twin desks of the cashiers... obliging one of them to press his head down on the table and stretch his arm extensively under it, walking his fingers up and down the dirty floor as he fumbled to find the card.)

“Pardon me, ma’am,” I said politely, “there is a queue here.”

I am not sure what she snarled in response, but if you saw the movie Alice in Wonderland, you’d know what I mean when I say that she was the Bandersnatch in a bad mood.

In cosmic payback, someone ran his shopping cart into the soft, painful part at the back of her ankle. The Bandersnatch turned and bit the gentleman's head. As she whipped her bulk around, she upset the centre of gravity of yet another person who was also shoving to reach the cashier. He dropped his shopping bags. One of them contained eggs.

I asked the cashier, "Would it not be better for you if you asked people to stand in an orderly line at this desk?"

"What to do, saar... the customers are asking for service so how to tell them anything?” he replied, bringing into focus the Indian sense of karma that Wendy Doniger described so skilfully in the preface to her potboiler, "The Laws Of Manu".

As I waited to sign my credit card slip, I felt like I was in an orgy scene scripted by a sadist who wanted to hurt filmgoers. There must have been at least twenty people heaving and shoving and pressing upon each other at the cashier’s with regard for neither politeness nor propriety. Nor deodorant.

Yet, in twenty years, someone else will write a nostalgic account of life in Bangalore and he will leave out the Bandersnatch.

He will write about how auntie Mavis made wine from turnips bought from Russell Market; and how the family giggled gently into the evening, telling soft tales to one another, but there will be no mention of the unsophisticated argument with the autorickshaw driver who asked for meter plus half.

"Bloody cheat, man, this fellow!"

Nor how uncle Vijay got into a fight with the neighbour after too much turnip wine and how cousin Anil was arrested after he stole money to feed his cocaine habit.

Was Bangalore any different, any time in the past, such that it should evoke the nicest nostalgia?

If respect for another’s space, civic sense and good manners are inherited—or learned—through family and social behaviour, the masala-minded loutishness of a city’s population cannot be the folly of one generation.

When I read historical accounts of the city that sport gentle descriptions of life of our previous generations, it tells me that someone is trying to be RK Narayanan; but the writer does so without the humour and without a roadmap to his fiction or selective truth.

And we never hear of the underside of the city, as we do about Mumbai.

Very often, the narrative of the city has always been in the manner of Dian Fossey recording her account of her years with the gorillas of Rwanda: with the love that one feels when chronicling the goings-on of a lower form of intelligence.

The difference is that Fossey chronicled her present. Bangalore ‘nostalgists’ chronicle a past that lives on in their minds. And they present us with such descriptions of the city that we can celebrate while doing our best to ignore the traffic, the garbage and B.PAC.

It might be appropriate to contemplate the last entry that Fossey made in her journal before she was murdered, which read, "When you realise the value of all life, you dwell less on what is past and concentrate more on the preservation of the future".

--------------------------------------------------------------

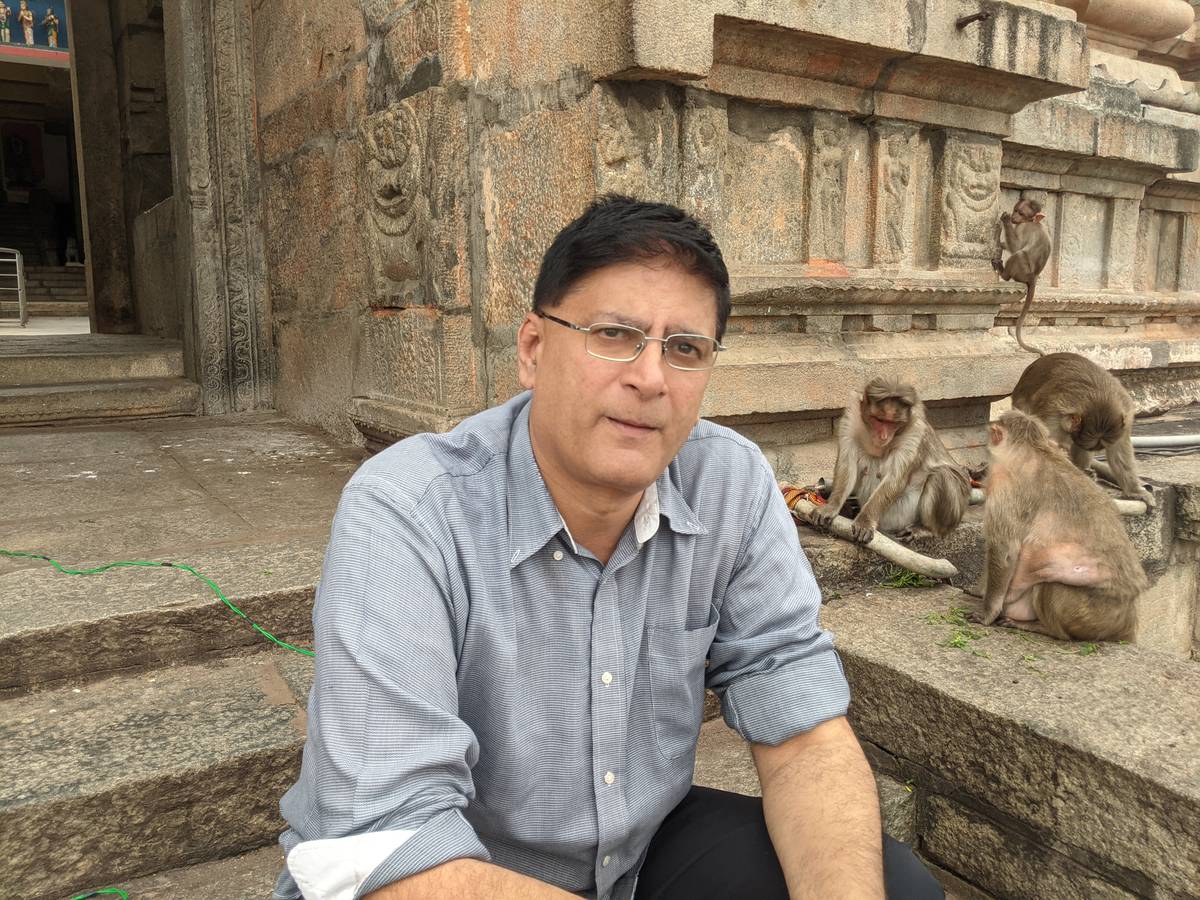

Ramjee Chandran is Editor-in-Chief and MD of Explocity.

rc@explocity.com (E-mail)

@ramjeechandran on Twitter