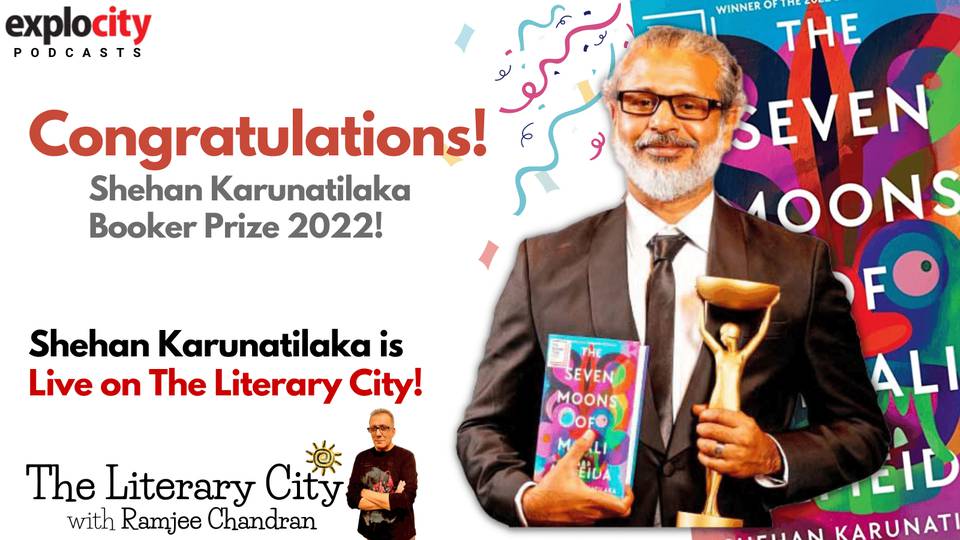

Transcript of podcast featuring Shehan Karunatilaka

Karunatilaka is winner of The Booker Prize 2022 for his novel The Seven Moons Of Maali Almeida

Nov 04, 2022, 17 09 | Updated: Nov 07, 2022, 20 35

The following is a transcript of the podcast with Shehan Karunatilaka on Wednesday 02. November 2022—about 10 days after The Booker Prize award ceremony.

The transcript is right after the podcast embed below.

You can also listen to the podcast here:

Listen on Spotify

Listen on Apple Podcast

Listen on Google Podcasts

Listen on The Literary City home page

Click here to buy The Seven Moons Of Maali Almedia

TRANSCRIPT OF EPISODE #44—Winner of The Booker Prize 2022 Shehan Karunatilaka

RC: Ramjee Chandran, host of The Literary City

SK: Shehan Karunatilaka

SK READS AN EXTRACT FROM THE BOOK

The chances of finding a pearl in an oyster are 1 in 12,000. The chances of being hit by lightning are 1 in 700,000. The odds of the soul surviving the body's death, one in nothing, one in nada, one in zilch. You must be asleep. Of this, you are certain. Soon you will wake.

And then you have this terrible thought, more terrible than this savage Isle, this godless planet, this dying sun and this snoring galaxy. What if all this while, asleep is what you have been and what if from this moment forth, you Malinda Almeida, photographer, gambler, slut, never get to close your eyes ever again?

You follow a throng, stumbling through the corridor. A man walks on broken legs. A lady hides a face of bruises. Many seem dressed for a wedding because that's how undertakers decorate corpses. But many are dressed in rags and confusion. You look down, and all you see is a pair of hands that do not belong to you. You wish to inspect the colour of your eyes and the face you are wearing. You wonder if the lifts have mirrors. It turns out they barely have walls. One by one, the souls enter the empty shaft and fly up like bubbles in water.

This is absurd. Even the Bank of Ceylon doesn't have Forty-Two floors.

“‘What's on the other floors?’ you ask anyone with ears, checked or otherwise.

“Rooms, corridors, windows, doors, the usual,” says a particularly helpful Helper.

“Accounting and Finance,” says a broken old man leaning on a walking stick. “A racket like this won't fund itself.”

"It's all the same," wails the dead woman with the dead baby. "Every universe, every life. Same old. Same old scene."

You rarely dream, let alone have nightmares. You float along the edge of the shaft, and something pushes you. You scream like a horror movie damsel as the wind takes you skyward. You are startled by the figure in black, floating behind you, its cloak of black garbage bags fluttering in a feral wind. He watches as you ascend the shaft and bows as you float away.

You try another question and ask what The Light is. But all you get are shrugs and insults. The frightened child calls you a ‘ponnaya’. An insult that alleges both homosexuality and impotence, and you will plead guilty to only one of these charges. You ask the staff about The Light and get a different answer each time. Some say heaven, some say rebirth, some say oblivion. Some like Dr Ranee, say whatever. The options hold little appeal for you, aside from maybe the latter.

At Level Forty-Two is a sign with one word on it.

CLOSED.”

RAMJEE CHANDRAN MONOLOGUE

There is an old saying, "dead men tell no tales".

But how wonderful and useful it would be if we could follow a conversation into the afterlife.

And what more wonderful than if you wrote about this idea and then won the Booker prize for your efforts?

Is this the stuff from which dreams are made?

Clearly, if you consider my guest today, Shehan Karunatilaka, winner of the Booker Prize 2022.

In Shehan's novel, The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida, the main protagonist, Malinda Almeida, is dead, but his character lives on. The novel set in a terrible patch of Sri Lankan history, between say, 1983 and 1990, is the story of a photojournalist who dies; and in the afterlife, he finds himself in the “In-between”, which is a state between “Down There”—which is life on earth, and “The Light”. And where The Light is is revealed at the end of the book.

The protagonist is confronted by, of all things, a bureaucracy in the afterlife. And he is told that he has a week—or seven moons—to find out how he died, if he was going to make it to The Light.

The novel touches the reader in many ways, not the least, to wonder what happens if we were indeed to find bureaucracy in the afterlife. Even the disappointment that visits us upon such a proposition is not rational. And yet...

Shehan uses the second person as his literary tool. Literary fiction written in the second person point of view is not unknown, but it is rare. This style is unusual because the narrator tells the story to the reader using the personal pronoun "you".

Shehan Karunatilaka's prose is compelling, gripping, even the turns of phrase and word coming together like playdough in what seems to be an absently crafted sculpture. Intelligent prose is never without its humour, and Shehan's prose has a river of funny as its undercurrent.

Try these:

He defines a queue in Sri Lanka as "an amorphous curve with multiple entry points." Clearly this is a South Asian malaise.

And this.. "the afterlife is a tax office and everyone wants a rebate."

And this one, "you drift among the broken people with blood on their breath."

All this, and you're still on page ten.

But humour is peppered through the entire narrative. And some of it is recognisable to typical snarky South Indian humour, like this on Page 135, "...he wore a frilly shirt tailored by a blind man."

In the context, though, the humour is a noir humour that characterises places in the world that have been in strife, such as Ireland, parts of the Middle East, and Shehan's home country, Sri Lanka. I really cannot wait to ask him about all this.

At the time of this recording, Shehan has just won the Booker Prize, just a little over a week ago. I know that the entire world's media waits to talk to him, and for this reason, I am particularly happy and grateful that he chose to spend all this time with me.

So here he is from his digs in London.

THE INTERVIEW

RC: Shehan Karunatilaka, welcome to the Literary City.

SK: Thank you, Ramjee.

RC: Usually I get about a week to research an author and read their book or books. In this case, the interview was fixed up yesterday, so I had less than 24 hours. And I read your book in one sitting.

SK: Oh, wow.

RC: But I also must say that I wouldn't have read this book in any other way because it was that gripping.

SK: I wish it was that easy to write. I wish I had written it in one sitting, overnight. But no, I'm glad to hear that. That's, that's very kind of you.

RC: [laughs] But reading this also gave me the chance to catch up on a whole lot of associated reading, like the history of Sri Lanka and so on. So all in all, very good.

SK: So you've been getting less sleep than me, by the sounds of it.

RC: Helps to be an insomniac.

SK: Yeah.

RC: Like yourself. I imagine.

SK: [laughs]

RC: To plunge in directly in. You are 47 years old, and Sri Lanka has been in some continuous turmoil since the mid 80s.

SK: Yes.

RC: That's pretty much your cognisant adult life. You grew up in that sort of news cycle. So no matter what your youthful distractions might have been, doesn't this sort of thing go straight to your DNA?

SK: Yeah, well, we grew up with… I was... I was really sheltered from the conflict. I lived in a Colombo middle class home, and we were aware of the war going on. Bomb blasts, assassinations, curfews and school closing down and stuff. But you could function unaware of the war. And that's, that's what my first book, “Chinaman”... I gave a brief to myself that, "...can I write a book about Sri Lanka that doesn't feature war or ethnic conflict?" And therefore wrote a book about two guys who just watched cricket and drank arrack throughout the 90s. Which is not a bad thing to do, because that was the start of a golden age of Sri Lankan cricket. So… so… I often felt removed from this, though… though it was all around me. And it's really… but I grew up with the idea of perpetual war. That's something that we… I mean, if you trace it back to 1983, I was eight years old then, and the conflict all through my teenage years. And then, you know, as a young man, I came back to Sri Lanka after studying abroad. And again, we live with this idea (that) this war will never end. We had so many false dawns. So I think that was, it stayed in my DNA, for sure.

RC: Over the years, speaking to people who have grown up in difficult zones, like parts of the Middle East or Northern Ireland, there's one thing that came across is what I just said: from childhood, they were born into this news cycle of strife and war. And you guys... it hasn't eased up at all, hasn't? It's one thing after another. And now the economic problems.

SK: So that's… that's my explanation that there are these, these spirits, these restless, bored spirits wandering around the afterlife, whispering bad thoughts in people's ears. That's my only possible explanation why we go through so many... I mean, I'm talking about 1989, which feels like ancient history, even though it's, what, 30, 40 years ago. And since then it's, it's almost forgotten because we've had so many catastrophes since then. And I mean, this year is a prime example, but before that we had the Easter attacks.

RC: Yes, that too.

SK: And it just seemed… and you know, we had a tsunami. I mean, I suppose that was the one thing that wasn't of human construction.

RC: Right

SK: All the other tragedies have been, have been manmade. So yeah, that was another sort of absurdist view that maybe it's because of all these restless ghosts that Sri Lanka seems to be going through this. But yeah, you're right, this is something we have lived with, but I've also, you know, lived with… it's not a dispiriting place, even today. I'm sure when you go back, there's a lot of hope that things have stabilised. It's better than it was... the chaos of three months ago.

RC: Right.

SK: And that… and there is a hope that there will be a new generation of leadership coming up and not repeating the mistakes. I mean, this idealism, we all suffer from it from time to time. But that seems to be the Sri Lankan experience. So it's obviously a fascinating place too, to, to write about. It's also a fascinating place to live in, though… it's… we live with anxiety and in uncertainty all the time.

RC: Right. I once had the experience of hiring two Sri Lankans in my Dubai bureau, which I had at the time. One was a Sinhala… Sinhalese… Sri Lankan and the other was a young Tamil boy who had run away from the LTTE after he had got weapons training…

SK: Oh wow

RC: ...and, and so on. And the conversations that I've had with them were fascinating.

SK: The two guys that you employed… did they become friends or were they arguing constantly? Or were they cracking jokes?

RC: No, no. Cracking jokes all the time, usually at my expense. And the only conflict that they had was to gang up on me. You were right about the humour, though.

SK: [laughs] So there, it shows Sri Lankans can coexist. Oh, and we seem to do it very well outside of Sri Lanka. But yeah, in Sri Lanka we seem to drum up all these conflicts.

RC: Right. Well, out of conflict comes humour. Great examples being Catch 22, Good Morning America. So many. And that sense of humour in your book is very, very typical of that noir humour that comes from us from a situation of strife. Would I be totally wrong?

SK: I think I take it back to the Sri Lankan smile.

RC: Oh, yes.

SK: Which is used by… I worked in the advertising industry. I, I still work, as far as I know, I think I still have a job.

RC: Do you?

SK: [laughs} And there's a lot of things to decide in the next few months… but yeah, the Sri Lankan smile is something we export in our tourist brochures, our airline ads, the fact that we are warm, genuine hospitable people, which is true. I'm not denying that. And you know, even in our cricket team, we have the smiley, happy-assassins, image.

RC: [laughs]

SK: Now, I think that is all true. But also the smile… it's a bit more sinister. I have deconstructed it. We smile when we're confused, when we're angry. We don't like confrontation. So instead of having an argument or saying something is wrong, we might smile and evade it. So it is used also as a weapon to disarm the opposition or avoid confrontation. And I think the humour is... is an extension of that, that we are, we are in these circumstances, these very serious, grim circumstances. But yeah, it would be, we would joke about the most grim things, even the cricket team losing often. Obviously, we'll get passionate about it. But if you witness my friend, Andrew Fidel Fernando, who writes for Cricinfo…he's watched the team lose for the last ten years, but he seems to mine humour in every tragedy. And that's why I keep up with Sri Lankan cricket, just to read Andrew's articles. So I think this is, this has been a feature. And most, and my, even my literary inspirations, I go to. I admire Ondaatje and Romesh Gunasekara And so on, who are very serious, elegant writers… not a great deal of jokes compared to Carl Muller, who I really draw from. Carl Muller's The Jam Fruit Tree and the Burgher Trilogy…

RC: Yes, of course.

SK: That was really… that bawdy sense of humour. And written in this very crude Sri Lankan way of speaking, I really drew heavily from that for my first book, Chinaman. And even though both the books are quite sad stories, I mean, Chinaman's about an old man drinking himself to death and Maali Almeida is about a murdered journalist who wakes up dead… both their characters see the absurdity of Sri Lanka and, and, and they crack jokes about it. And I think the example of that is, if you look on Twitter or on TikTok, and look at how the “aragalaya” [Sinhala for “struggle”] and 2022 has been covered. And even the political cartoonists were really at the top of their game. So throughout the economic catastrophe, it just seemed like this was a weapon in which to mock the ruling class, the ruling family, which didn't exist in 2010, 2011, 2012. Right after the war, we really feared this regime. Journalists would go missing and assassinated in broad daylight. And white vans were reality. If you speak up, if you say the wrong thing, you'll be taken in. So we went from that climate of fear to openly mocking on the internet. So whenever a politician makes a claim on Twitter, they pile on. And most of the responses are quite humorous. And you saw in the Aragalaya, people on the streets, right? So, you know, and so I think humour just emboldened us. And the fact that we were able to laugh… and even the petrol queues that we experienced, and, you know, still have not completely vanished. Those places were, well, quite fun place, you know, people were playing cards. And of course there would be arguments. There would be tensions, obviously. So I think this is a defence mechanism. And I'm interested that you see it in Ireland and in the Middle East as well, this idea... that you, you have to laugh at your predicament, because otherwise what else we know what happens when we get serious and angry. Sri Lankans, then we're not all happy, smiley. We're capable of quite brutal things. We know this. Might as well tell a few jokes and get by rather than the alternative.

RC: I dare say… Well, on a happier note, congratulations on the Booker Prize. Seven Moons of Maali Almeida. Has it all sunk in? It's just been over a week.

SK: It has been over seven moons since, yeah.

RC: [laughs]

SK: Because the whirlwind... I'm in the world when I had some a bit of a rest, but it's coming to grips with the fact that now I have a career as a writer, which is not something you take for granted after one book, you know. We all have day jobs in some form or the other. And you think this is something you're going to devote your effort and time to. But now the reality is, yeah, this book has been widely read. It's selling well. It's been translated, and I think Chinaman will also follow soon.

RC: Yes, of course.

SK: So, yeah, but it's not something when you write, you expect. Especially writing in a small room in Colombo, about a very specific conflict, or very specific cricket team. And you don't, you know, they are fantasies of these… you just think, let's make the next book better, and let's hope it gets published more widely.

RC: And so tell me about the journey. Fun? Fulfilling?

SK: It's been step by step, you know, you take a Booker longlist, you of course you know, that means the book will see more reviews. So I took it and so I came to Monday night delighted to be part of this brilliant shortlist. Because there were quality books all from the long list onward. So I went with that mindset and it was a low-stress evening. In terms of, you just have to wear a suit and, you know, eat and drink and talk to people, chat with people. There wasn't any big speech to be given unless your name gets read out. But it would have it, that once their name gets read out, then you sort of click into autogear. You think, okay, do I have my notes with me?

And then, so then it's just been five days of relentless live interviews and so on. So it's like, now I've had some time to, yeah, just sit with friends and sit with the family and just talk to talk to people and understand this. Yeah, it's a wonderful thing. But I would very much like to get back probably naively. I talked to Damon Galgut. He said, my friend, you're not going to write a word in the next twelve months. Don't expect to. I hope to prove him wrong, but, you know, you know, but I, I'm going to enjoy this.

RC: It all still must be quite heady, right?

SK: Yeah.

RC: Now to plunge it into the book, I don't think I have read another book that is dystopian in the afterlife. Your protagonist is confronted by a bureaucracy. These lines from page 90: "...when you fantasised about heaven, you thought you would be greeted by Elvis or Oscar Wilde. Not by a dead professor with a ledger book."

I've noticed that many creative writers consider the bureaucracy an enemy, whether in this life or the afterlife.

SK: Well, I live in Southeast Asia, so I've been a victim of it every time. But I mean, it's got better. My UK visa arrived much quicker than I thought. I suspect I won't have that many problems, at least for the next twelve months.

RC: I suspect, from now on.

SK: Yes. But for me, I was just looking because I had to.. .this was one of the challenges of this book, I guess, a big technical challenge, is, how do you envisage the afterlife? How do you make it convincing?

We have this naive notion that when we breathe our last and open eyes again, everything will be revealed. It will all make sense. And, you know, this is all wishful thinking in our view of, yeah, how we envisioned heaven and the and so on. And, or how we'd like to be reborn, or who we were in the past. There's a lot of wishful fulfilment in it. And I just thought it made more sense that you open your eyes and it's as confused as it is down there, you don't know. And so that it was an absurd enough conceit that I could mine humour from it. But also, it just made sense that this is why ghosts are all these restless spirits, because they haven't got the right piece of paper with the right stamp from this place.

RC: How interesting.

SK: And like I said, it made sense. It it was a possible explanation of why Sri Lanka seems to be plagued with tragedy, is because perhaps they are all these restless spirits. So, yeah.

RC: And the central idea being?

SK: The idea that the afterlife is bureaucracy, and God is on his or her lunch break and hasn't turned up for millennia. I just seemed to make sense of this absurd worldview. So if there was an afterlife, it should be as chaotic as anyway, it was a good place for me to do this puzzle of a novel. So he has to kind of unravel the rules of the afterlife in order to achieve his goals of solving his murder and exposing his photographs. But yes, bureaucracy is...

But one thing I have to say, without being flippant, over the last years, Sri Lankans have learned to queue. That's what we have acquired. So my 1st chapter is already dated, where I kind of poke fun of the Sri Lankan queue.

RC: Like the line I read out in my monologue.

SK: Yes, yes, you have to kind of elbow your way in. But now petrol, gas, whatever, people queue and breaking the queue...there are still queue jumpers, but they get dealt with sternly. So at least that's something that has come out of this.

RC: A South Asian malaise, I dare say.

SK: [laughs]

RC: Now, in your book, your character is solely responsible for his journey from “Down Below” to the “In-between” to “The Light”. I hope this isn't a cliched question already, but is this the case of 'all Aeneid and no Virgil?'

SK: All Aenid [laughs]... okay, so I read Dante's Inferno as preparation, and I think everyone should read that.

RC: Oh, yes.

SK: So… so, yes, I guess similar. Do I recall… who was the poet? It was, was it Virgil who was…

RC: Yes, it was

SK: ...who was signposted as a guide right at the beginning of Dante's Inferno version. We are mangling our classical references…

RC: [laughs] No… no… it is Virgil, the blind guide. Virgil, it's always Virgil. I mean, that guy is a real Forrest Gump.

SK: [laughs] But look, it's quite, mine is quite simplistic. There's no seven circles and so on. But the light was something that I just found. It's there in Judeo-Christian or Christian mythology, even these documented near death experiences.

RC: Oh, yes.

SK:All talk about the light and a familiar figure advising them.

RC: Oh yes, that's all true.

SK: The light, you know, perhaps it's revealed late in the end of the book what it could be. But that was a nice symbol and a vague enough symbol for me to have the goal at the end of “...Seven Moons”.

RC: Yes you reveal what The Light is at the end of the book. No spoilers here. But to me, the novel ends on a note of hope. It's a dystopian novel with a happy ending.

SK: Okay.

RC: Hopeful.

SK: Yes.

RC: Now let's go to some of the craft that you use in the book. The second person narrative. Planned or did it just happen?

SK: So the second person, I think all my books, I mean, they've only been two, but I've tried writing in the third person. I always attempt the first draft in the third person. It ends up then the first person one was an unreliable first person narrator. And this was second person. I think, again, a technical problem to solve. Like, what does a disembodied voice sound like? And I couldn't,... he no longer has a body.

SK: And how do I describe and locate the person? And I just thought that the theme that if, if anything survives the death of your body, it perhaps would be the voice in your head. Now that could be the voice of your conscience or your soul or whatever. But the voice in my head, I don't know everyone else's, but the voice in my head is predominantly second person. You know, it talks to you like a coach or like, like someone else telling you, you know, why did you do that? You should have done this. And anyway, I just tried it out.

And I think that's the test really with finding the voice of the book. With the first one, when I decided to tell the story from a drunken uncle's point of view, that's when suddenly I had fifty pages in a few weeks. And you knew it was working. You were interested in exploring that. Similar thing happened here when I switched to the second but rather than the first person, which implies that it's Maali having this experience. Second person almost implies that it's something bigger than Maali. It's his. I mean, you know, that's also explored. So I won't explain too much there.

But so the idea is the voice of the conscience and, and what's interesting is now we're doing the audio book, and I've noticed the voice talent uses a slightly different voice when narrating. "you are sitting at the counter", when Mali speaks, it's a slightly more accented voice. And I thought that was quite clever because I never, you know, I subconsciously realised that the narrator and the Mali acting are slightly different. They may be the same soul, but they are slightly different.

RC: How interesting.

SK: And so, yeah, so that's why, so there was a lot going for the second person, but also just seemed to move on the page. And it's quite a challenge. You know, it does get irritating if you don't do it properly. So I had to check that. But yeah, I... I went with it because it just the, yeah the pages started flowing in, the story started telling itself. So that's the reason why.

But I think it makes sense as this is the voice of the voice in your head.

RC:I think it totally worked. No cracks in the floor. Another part of craft... you were writing a whodunit, but set in a complete fantasy land. Now, when that happens, you can make up any rules of engagement that you like, but you must make some rules of engagement mustn't you? Was that a challenge?

SK: Oh, yes, yes, for sure. I mean, this took a good seven years. I think, interrupted by the arrival of two children, but also, yeah, so that's my excuse. I mean, they're eight and five now, you know, they're so that's why the novel took so long. Hopefully the next one won't because they are better behaved.

RC: [laughs]

SK: But yeah, I mean, so I kept and also, I used to work in Singapore, I used to fly over to Singapore for a few months to, you know, earn a living. And so there are lots of stops and starts, so each time… but yeah, I did try and construct this, the rules of the afterlife.

And in the end, we just discarded, there are lot of different rules about, you know, temperature, controlling the temperature, controlling insects, all these things that we associate with ghostly haunting.

RC: Right.

SK: But in the end, just the few important ones was the time frame of the seven moons that you had to resolve everything. And also the fact that, yeah, you, you had, you could only go with you where your body has been. You could only travel by wind, and you could only go where your name is spoken. Which allowed when you're having a murder investigation. Maali could quite logically go whether he was being discussed. And it's, it's also another thing that I've seen in literature, the idea that you die a second death when the last person on earth speaks your name. So I think I took all these different borrowed elements, but in the end, I think those are the main three rules. We discarded a lot so it didn't get complicated.

RC: Okay.

SK: But yeah, you're, you're certainly right. A reader won't forgive you if suddenly, the guy has a superpower that you didn't foresee.

RC: I confess, I was looking for these cracks, but I couldn't find any.

SK: Yeah, no, no, I think this is also the value of having a wonderful editor.

RC: Who was your editor?

SK: So this is Natania Jansz who I should give more credit to, because she edited the book with me over the pandemic. And initially it was just to make it more accessible to a wider audience outside of the subcontinent. So to explain the complex politics as well as the mythologies. But I think in the end, we were looking at all of these things-pacing, how the different elements and layers set together, that there wasn't too much confusion and noise, but also the consistency of his quest and his journey as well. That's the reason why the afterlife was able to remain consistent.

RC: And now a little about the language you weave in the local dialect, in the spoken voice. Here's one. "You all have seven moons"... “You all”.

SK: I think the first book had a lot more… a lot more pushback from editors. I mean, slang is one thing, but it's also syntax and word choice. And, you know, "let's put a drink" is what you say. You don't say, "Would you like to join me for a drink?" “Shall we ‘put’ a drink?”

So I mean, I realised how much there was when I had to… for the audio book read… do a pronunciation guide. And usually pronunciation guides are of one page, this was like over 20 pages, 400 terms that I had to pronounce.

RC: Amazing.

SK: So I think in the first few drafts, you're just trying to talk as authentically as the character. Then you come in and you think, okay, is this going to confuse readers? But I think in most of the case, I think perhaps in all of the cases, the context, even if you don't know what a particular… what ‘Mara’ means, you can look at the context and know that it's an intensifier. He's saying that's very but it's sort of and so I think we just did that check.

RC: Euphemism, this one from page two, six. "He is a bit of a left handed batsman." Is that a gay reference?

SK: Yeah, so that's a Sri Lankan... "Confirmed bachelor" is the other one. “Confirmed bachelor, that fellow…” You know, “he's a 'confirmed bachelor'”. And left handed batsman is another euphemism for that...

RC: Colourful

SK: And “Bats for both sides”, or yeah…

RC: Euphemisms of old. Now let's go to another side of you. A lot of people will be delighted to know that you are a bass guitar player in a rock band. That's another thing we have in common. I play jazz guitar.

SK: Oh, wow. That's proper guitar with proper jazz chords. No, I was... I used to just play power chords.

RC: And I think you're being modest, because I just heard a song that you recorded with your band Powercut Circus. It's called Red Spit. I really enjoyed it. And I'd like to talk about the lyrics from that song. Goes like this.

"I'm thinking about the news, I read this morning | More people dead, more people missing right under the cops noses | Fat politicians are impotent posers..."

Tell me you wrote those lyrics.

SK: No, I didn't. The drummer wrote the lyrics for this band. So this is cool. Yes, yes. Powercut Circus.

RC: Powercut circus.

SK: Quite a... you know, underrated. So, you know, look, I, I was, came from the grunge era, the punk ethos. So I didn't know Lydian and things, you know, we just had power chords and we played… and, you know… I think that was something. We are proud of them, but I'm not so proud of them now, because I wish in my youth I had actually learned proper jazz guitar and how these things work. But I think once I came to this band, Powercut Circus, I very much wanted to be a bass player. So I saw myself as a failed guitarist. And I just did that.

I just... we... and our songs were sort of jammed rather than constructed. You know, you come with a song. And I remember the drummer, everyone used to write lyrics. And for some reason, I think I was probably writing Chinaman at the time. I didn't write that many lyrics for this band. And so, yeah, Dhinesh, the drummer, Dhinesh Manuel, who's… who was the great talented drummer. He wrote this, this, I suppose it's a poem almost about just walking, yeah…down Galle Road and during the time of checkpoints and which, you know, seems like so long ago and it wasn't real. It's less than 20 years ago. So no, I didn't write these lyrics. It was him.

RC: But they do fit the current narrative.

SK: They certainly do. Yeah. And I fantasised about being a great musician, not about being a great writer. But the thing is, I, wrote every day. I didn't play guitar every day. And that I think is telling. In my 20s, I, for some reason I would write every day, even a diary entry or something. But I didn't pick up my guitar unless I had a gig. And I think that's telling where my musical... whereas now I'm using it as a tool while I'm writing. So yeah, I bought myself a piano during... or a keyboard during the pandemic. I just bought myself a drum kit just before I left for Booker as a gift to myself. So yeah, I, you know, and now I play a bit of guitar and so, you know, when I'm taking breaks during the day, I'll play some scales and all that.

RC: So do I have your permission to play Red Spit at the end of this podcast?

SK: Sure, sure. I should ask the other guys, but I don't think they'll have any problem. No one's been asking for Powercut Circus tracks.

RC: They will after this podcast.

So for our listeners at the very end of this podcast, right after ‘What's That Word?!’ there's a treat featuring Shehan Karunatilaka playing bass in…

SK: Red Spit by Powercut Circus.

RC: Yes, Red Spit by Powercut Circus.

SK: That's a great name. Powercut Circus. We were thinking of resurrecting it

RC: You should.

SK…because it makes sense for 2022…

RC: And there's a link in the podcast description to where you can buy the book. Seven Moons of Maali Almeida, Booker Prize winner 2022.

SK: Fantastic.

RC: A couple of quick things before we go. I remember reading somewhere that you once said about a description of yourself some years ago in the Galle Literary Festival that you were crawling all over Unawatuna beach offering massages to anyone with a printing press.

SK: That was a while...

RC: I dare say that those with printing presses will be offering you massages.

SK: [laughs] That's true. Well, that's a long time ago. When I just finished Chinaman, when I was looking for someone to... I was self publishing it. Yeah. So I was looking for printers rather than publishers. Yeah. Quite a long time ago. You're going back to Red Spit days.

RC: Days that I dare say that you probably will not leave behind. Now, your next book is called The Birth Lottery. I have a copy, but I haven't read it yet. I will. And I hope that you will come back on the show to discuss it.

SK: Of course Yes.

RC: Congratulations again on the Booker prize and Shehan Karunatilaka, thank you so much for being my guest today on The Literary City.

SK: Thank you, Ramjee. Was a pleasure.