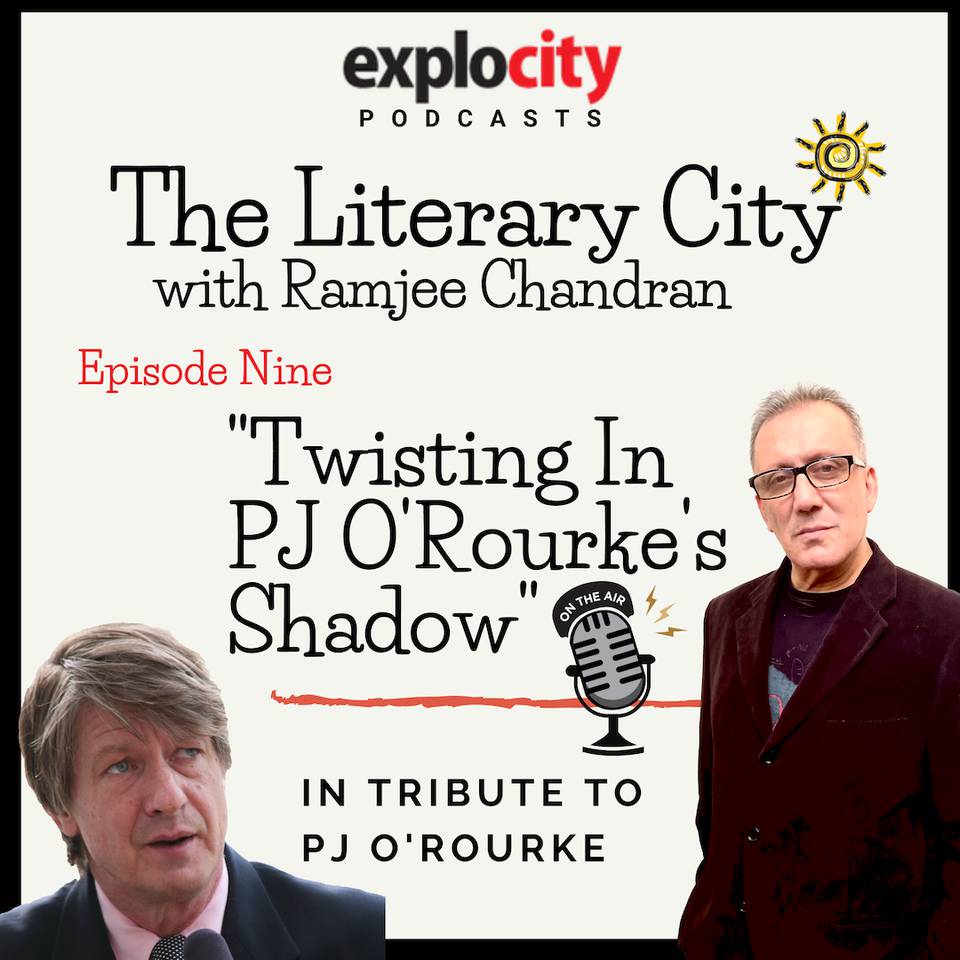

Twisting In PJ O’Rourke’s Shadow

Maybe because writing in America requires you to be bicameral in your examples, O’Rourke wrote that god is a Republican and Santa Claus is a Democrat.

Feb 23, 2022, 00 37 | Updated: May 22, 2022, 11 50

This is a transcript of the Episode from the podcast, The Literary City With Ramjee Chandran. Season 1, Episode 9. It is a tribute to the great political satirist PJ O'Rourke, who passed away last week (February 2022.)

LISTEN HERE (No login required)

Twisting In O'Rourke's Shadow on The Literary City With Ramjee Chandran

It would have taken little for me to travel from New York to New Hampshire to meet PJ O’Rourke, my favourite writer. It’s something I always wanted to do but never did. So instead of the scintillating conversation that I thought that I would have—with a side benefit of education for myself—all I have to offer now is this eulogy.

I decided I will do this tribute to PJ O’Rourke entirely from memory.

The way I see it, if I cannot remember the words of a writer I claim to be able to eulogize, then I shouldn’t. I am old school enough to believe that one should not write a tribute to someone if they find the need to google the details.

Consequently, my quotes are not precise. I dare say not even correct in places; and the trouble is I don’t know in which places.

So, left to my own memory, I must try to convert this eulogy into entertainment and squeeze out a laugh when the literary world calls for a tear.

A tear because Mr O’Rourke died last week.

There is always something unreal about people you admire, dying.

Even more unreal when they have been a part of your life and you have never met them.

It is one of those pop psychology things, (I call it popcorn psychology things), where they have broken down grief into a convenient listicle - you know, Denial, Anger, Bargaining, Depression, Acceptance.

Grief for Dummies.

And maybe because the 5-item listicle itself might be too long to hold a listener’s attention, someone I know sliced off and cobbled together the first letter of each word into a bizarre acrostic and popcorn’d it further into…DABDA.

DABDA…

An adenoidal sound… nasal consonants spoken with a clothespin clamped to your nose.

Actually, that’s not a bad idea. I think all listicles must be handled with a clothespin affixed to one’s nose.

As soon as I heard that PJ O’Rourke had died, I did what people do normally.

I went immediately to my library—which is a fancy way to describe a few untidy bookcases with books double parked - and without being held together with a Dewey Decimal System.

I checked to see if I had all of his books. The spines of my PJ O’Rourke collection stood tall. None of them were dead and they were all still replete with his intellect and wit.

Weirdly, that was a rather irrational relief.

Anyway, back to grief, no matter how shitty you feel, finding your place in the -ugh- DABDA is convenient to everyone around you.

Instead of having to pretend to share your grief, they can stroke their chin and declare that you are in, say, in the Denial stage. And make sympathetic mouth noises while all the time wondering who PJ O’Rourke was and why you are his groupie.

PJ O’Rourke addressed death with humour. As he did everything.

In one piece — on the side benefits of drinking and driving — he explained how alcohol loosens up the muscles.

So therefore, if your car was to crash a barrier and roll down the hill and you died, how much less aesthetic you would seem to your grieving wife to see you stiff in your sobriety and mangled in the crash, rather than the lithe, limber curly ball you could be with booze inside you. She would be so much more comforted.

In another piece, O’Rourke poked a finger deep into the squishy mess that is senior mortality and made a joke — if you can call it a joke — that older people sit around waiting to find out what sort of cancer they would get.

Such is the insouciance of the youth.

Which would be age-appropriate if O’Rourke had been a youth.

And then PJ O’Rourke got cancer.

He apologised for his crack about senior people waiting to get cancer and started to reflect on his own mortality.

I remember this from an essay, titled, Give Me Liberty AND Give Me Death, when he addressed god thus (of course I paraphrase…)

“But God, Sir,” he opened, “aren’t your lessons about life’s consequential nature a bit extreme, pedagogically speaking?”

About life’s difficult lessons he went on to ask, “Dying is more homework than I was counting on. It sort of messes up my vacation plans.”

O’Rourke ruminated on death and asked why death—If we must have it—cannot be glorious and heroic as in the Iliad or like the fallen heroes of war as in Fallujah and Kandahar?

But in reality, he pointed out, death came more in the form of, say, an old person drooling in a nursing home, or someone crushed in a car crash or, I sort of remember this line, “Someone OD’d on drugs in a hotel suite…a minor public figure whose celebrity expiration date has passed.”

But I come here to praise O’Rourke, not to bury him.

If there is any one individual who kept me in this fantastic world of wanting to be a writer, it is PJ O’Rourke

From the day that I discovered his work, that was the case — I think I discovered him via a reference in Esquire magazine.

Esquire was at the time, the magazine of reference for literary journalism. Everyone that mattered totally OD’d on Esquire.

I have not stopped reading PJ O’Rourke since.

I don’t know—and I don’t really care—but I might even be an O'Rourke completist. Which means I have collected all his works.

I read his books. I have hunted down his essays he wrote for various magazines and I have read transcripts of speeches he made at the Cato Institute — the refuge of libertarians.

Although Mr O’Rourke is often described as a “conservative”—and he has much writing to testify to that—it is said that he was, at heart, a libertarian.

For those who might ask, a libertarian is one who believes in complete personal freedom and that even the slightest government might be too much government.

Those of us who have been raised in a very controlling environment—socially, culturally and politically—would find it hard to fathom the real meaning of freedom.

We—more readily—understand a democracy where a political party has come to power, typically through bribery, coercion or worse, through religious fundamentalism and empty-headed patriotism that even dummies can easily understand.

Libertarians don’t care about isms except the ism of being left alone to do their thing. O’Rourke was quoted as saying that the only human right is to do as you damn well please and the only basic human duty is to take the consequences.

But O’Rourke was not born into what you might consider right wing politics.

He was at first a Maoist. And a hippie in the 60s.

And then in the early 70s, he joined the magazine, National Lampoon.

In an editorial room full of Harvard graduates (they were all formerly of the Harvard Lampoon), he was a graduate from a school in Ohio called the Miami school. (Those with a smattering of knowledge about the States will see the irony in that.)

He rose to become the editor of National Lampoon only a few years after.

The most famous of his pieces while at the Lampoon was this dizzying ride, in gonzo journalism, titled, “How to Drive Fast on Drugs While Getting Your Wing-Wang Squeezed and Not Spill Your Drink.”

By the 80s, he was a Libertarian.

O’Rourke’s friends say that his near anarchist ideology came from a teeth-gnashing revolt against anything authoritarian.

But like many Baby Boomers, (those born between 1946 and 1964), he changed his political mind when he saw how much tax the government was taking out of his salary. And how little he was getting for all that.

He said, hilariously, that he had struggled for years to achieve socialism in America only to discover that they already had it.

He didn’t care much for government handouts. If you think healthcare, he said, is expensive now, wait until you see how much it costs you when it’s free.

Maybe because writing in America requires you to be bicameral in your examples, O’Rourke wrote that god is a Republican and Santa Claus is a Democrat.

If O’Rourke came into his political own sometime during the 80s, he is very likely to have been influenced by the era of Reagan politics and supply side economics and the tsunami of popular “the world is your oyster” writers of the day, such as George Gilder and Milton Friedman. And there were others.

But equally, I wager that O’Rourke influenced the trajectory of the conservative literary canon.

An interest in Economics led O’Rourke to discover Adam Smith’s “Wealth Of Nations” (first written in 1776) and to his own book about it, titled On The Wealth Of Nations—which is a fascinating read if only because it's a book on economics written by someone who is not a economist, but rather someone like us…someone who is trying to figure out what anything means.

In a Cato Institute speech, he said that he had reduced 900 pages of The Wealth of Nations into a more digestible precis of about 200 pages so no one would have to read Adam Smith. And now, he was giving a 20 minute lecture, so no one would have to read PJ O'Rourke.

The hallmark of intelligent observers is that they like to observe. They are always curious.

PJ O’Rourke was always curious and curious about the whole world.

The most fascinating stories from O’Rourke were from his travels.

There is one of particular interest to India—his trip on the Grand Trunk Road from Islamabad to Kolkata. He said the road was straight and narrow and would have been two lanes wide, if there were such a thing as lanes in India.

On that great Indian highway, O’Rourke joked that he had attained reverse enlightenment when his mind was overwhelmed by a sudden flash, but it was the blinding flash of an oncoming truck.

On the way from Varanasi to the West Bengal border he counted as many as 25 Tata trucks, “smashed into chapatis of carnage”.

His book, Holidays In Hell—a travel guide to the most desperate places on earth—was an account of trips that he took, voluntarily, to the craziest places in the world—countries torn apart by war and economic strife. This included looking for a good time in communist Poland and getting pepper-gassed by the cops in Korea at a student protest.

And then he joined Rolling Stone magazine. Not for the music, but as a war correspondent. More accurately, foreign-affairs desk chief.

In that time he covered the Gulf War — Iraq and Kuwait and brought to his readers an angle to being in a war zone that was dangerous, of course, but somehow was also funny.

There’s that enlightening passage where he talks about being embedded with the American troops in Saudi. I think it was Saudi. At any rate, a place where alcohol is forbidden.

The Americans who tend to be rather straight laced about the rules, had no alcohol to give the troops.

But the British troops were laced differently. According to O’Rourke, they would receive an unusually high supply of boot polish tins, all of which contained booze.

But not the Americans and so they remained dry and sober for the duration.

But O’Rourke, whose fondness for alcohol was legendary, found—that even without any substance in him—that he could still write…much to his amazement.

He confessed, “What I thought all along to be the pain of creative genius, was only a hangover.”

Being labelled a conservative changed nothing of his uniqueness, his singularity and his innately non-partisan approach to criticism.

He dinged both sides equally.

He once said that Democrats will tell you that government works and that the government can make you taller, smarter, younger, richer and so on. The Republicans will tell you that the government doesn't work and then, he said, they get elected and prove it.

As for being labelled anything, I have no evidence that O’Rourke called himself a Libertarian or called himself anything at all.

When you are sui generis, there is no need.

And in a time when political writing—even the funny ones—was generally pedagogic and boring, O’Rourke’s irreverence made everything more accessible.

Politics, like religion, has always been a Laugh Out Loud thing. How could anyone possibly take any politician seriously?

But that LOL thing, in O’Rourke’s writing, started to take a darker and more disquietingly disparaging tone as debates and disagreements in American politics started to take on those very shades, you know, with the emergence of extreme factions and the increasing acceptance of people who are under-educated without apology… people like Sarah Palin at the time.

And political engagement and critique was no longer a game played by the well-read and witty.

I imagine that the greater despair for O’Rourke was that his own milieu was starting to descend into resembling the politics of the countries he had all along classified as being shitholes.

And even that word, before it sets off Trumpian alarm bells, was, in PJ O’Rourke’s hands tinged with a warm and fuzzy humanity. And not something suspiciously racial.

O’Rourke had once stated that his humour was about poking fun at human foibles, not RXing prescriptions for improvement. That was definitely the tone of Holidays In Hell and that other wonderful book, Parliament Of Whores.

But with his new book, Don’t Vote, It Only Encourages The Bastards, his sense of the funny had started to include policy, even manifesto.

And with the advent of Trump, something that even a vocal conservative like PJ O’Rourke could not stomach, he went against his own advice and voted.

For Hillary Clinton.

He called her, I quote, “the second worst thing that could happen to this country” but he continued to say that while Hillary Clinton is wrong about everything, she’s wrong within normal parameters.

In his book, Peace Kills, published in 2004, O’Rourke wrote that “The idea of a news broadcast was to find someone with information and broadcast it. The idea now is to find someone with ignorance and spread it around.”

If anything, things have become worse.

O’Rourke’s sense of the non-partisan was of great appeal, across the political spectrum, chromatically, even when sometimes his views were grating.

One such grating example was when his sense of despair led him to see virtue in the Tea Party, if only because the Tea Party called its putative parent, the Republican Party, into frequent question.

O’Rourke was by no means a prescient political writer nor was he correct all the time. But he never allowed parochial thinking to taint his quest of impartial enquiry and comment.

And within that, he was certainly the most literary.

When I started this podcast someone asked me who I would most like to interview as a guest.

I did not hesitate.

“PJ O’Rourke,” I said.

And then I decided I should do something about it.

And I went so far as to score an introduction through a common friend in New York. And then I let him get wind that I might call him from India.

Right when I was about to call, I heard PJ O’Rourke went and died.

I want to tell him—just as National Lampoon would have done—that he could have simply said no.