A Successful Retailer’s Legacy - Mr TS Shanbhag Of Premier Book Shop

Whether or not this is a mark of someone’s success as a person — Indeed I wonder how many of those paying high tribute to Mr Shanbhag even knew him as a person — the accomplishment of Mr Shanbhag was that he was a successful businessman.

May 06, 2021, 15 29 | Updated: Nov 06, 2021, 17 29

Every old Bangalorean has a Shanbhag story.

And in his passing, everyone seems to want to claim him for their personal nostalgia.

Whether or not this is a mark of someone’s success as a person — indeed I wonder how many of those paying high tribute to Mr Shanbhag even knew him as a person — the accomplishment of Mr Shanbhag was that he was a successful businessman.

When you read everything written about him and question people about their love for this Bangalore landmark, they respond with a description of his store and of Mr Shanbhag, as its owner and manager.

And librarian. And curator. And a walking ISBN database, wrapped in a clairvoyant Dewey Decimal System of the mind.

It means he knew what books he had in his store and that he was able to find any book a customer asked for.

By squinting into the middle distance.

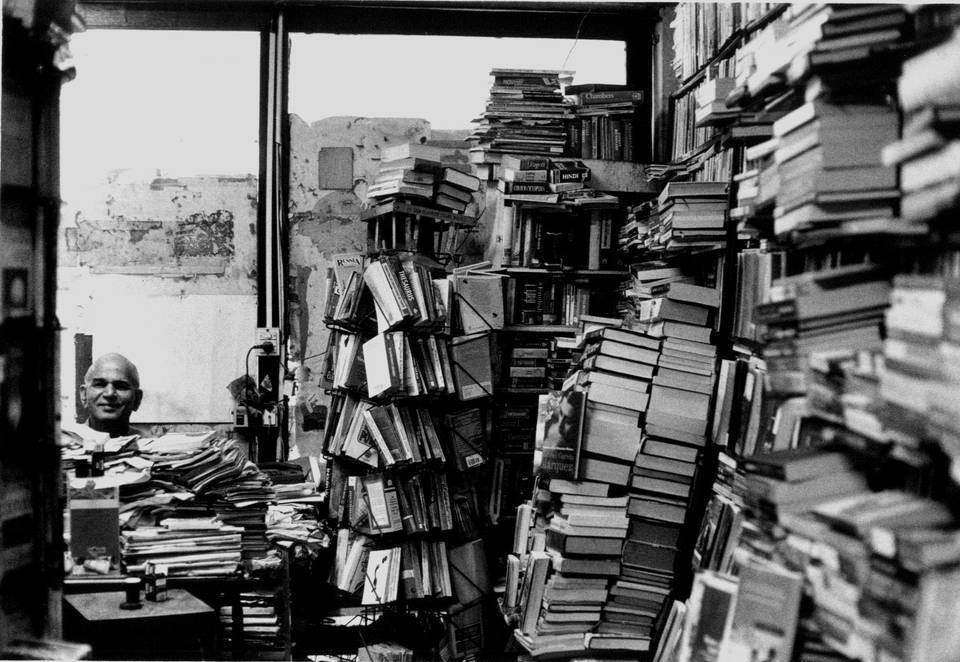

He would then walk over to a stack of books about nine feet high — I once measured this for fun — and find it nestled at the seven foot mark. He then would dust it off and give the customer a discount, even if that dazzled customer was willing to pay a premium for it.

His knowledge of his product — books, by titles and genres — was his strength.

When he knew — by dint of aforesaid squinting — that he did not have a book, he would offer a recommendation with the incisiveness of an astrologer who somehow zings you with a home truth.

So, even if he had not read “Zen And The Art Of Motorcycle Maintenance”, he had the ability to associate this title by its genre to “The Road Less Travelled” or say, “The Sutras Of Chanakya”, and then offer one of those as an alternative following a Holmesian — or is it Sherlockian? — assessment of your tastes.

That is a simple example but there are tales, more nuanced.

He also knew not to make a recommendation merely for a sale. In the late 70s, my Significant Other of the day, and I went looking for an anthology of the poet Alexander Pushkin, such being the pretension of the formative intellectual.

Mr Shanbhag did not make a careless recommendation, there being no alternative to this specific request. “Come back next Tuesday,” he told us.

Shanbhag’s astuteness was not literary. It was mercantile.

He knew his business and knew what drove his customers.

And so into his database we all went.

If you think about it, much of his surprising acumen must have stemmed from an algorithm similar to that Amazon uses to make recommendations: title, genre and buying patterns.

And in his case, what customers have said about a book and how to tell pleb from prole (this being a literary distinction that determined that Kamalahasan — or whatever his stage name is now — should be touted among the example customers.)

Window display and product placement were key aspects to his method.

He attracted the type of customers who were drawn to the higgledy-piggledy nature of all things intellectual. While the more modern bookstores have neat shelves and teakwood section signs, Mr Shanbhag created an appeal for Premier Book Shop that bore the romance of serendipity.

Books were piled to the ceiling and stacked seemingly at random. He gave the display a sense of discovery and because things were not spare and labelled, it was easy to lose sight of one’s goal and spend hours staring at the spines of books.

These romantic notions extended to Mr Shanbhag’s persona.

Mr Shanbhag sat near the entrance, always covered in bookkeeping impedimenta. Every now and again, the content of a file, usually looseleaf copies of indents and invoices, would slide over a stack of books in a journey to the floor and Mr Shanbhag would lunge with one arm to restrain the free flow of accounts documentation while answering a customer on where she could find a copy of Karma Cola by Gita Mehta.

The absent-minded mad-scientist mystique sat well on Mr Shanbhag. With his stock in trade seemingly scattered at random across the store, we subliminally embraced the perception that he was this booklover whose principal objective was to enable our literary positure — that he had simply piled books everywhere and let you find the book you were looking for, and in the process, your inner self.

And that, as a savant, he would find what you were looking for because he “somehow” knew where it was.

I knew Mr Shanbhag as a fallow college kid, buying Pushkin and Camus so I could become a better man, and some years later, I knew him from being a (fallow) publisher of a city magazine — The Bangalore Monthly — that sold very well at Premier.

I discovered there was nothing random about the way Mr Shanbhag ran his business and he was not short of being businesslike and was shorn of any “I am a booklover” sentiment. He asked me searching questions about the magazine’s positioning and told me he hoped I was going to make it a “real” magazine. I told him I was not planning to fill it with literary genius. He smiled agreeably.

By my experience, I know he was no absent-minded mystic. If there was no computer in the store it was not because he had an eidetic memory bordering on photographic, but because he was super organised and he placed his books in a logical order. He was extremely process driven and orderly.

Some great retailers are gregarious and fun — restaurateurs are typically this.

Some great retailers don’t blow a vuvuzela at every arriving customer.

But both always inspire loyalty. And business.

Like every good retailer, Mr Shanbhag could make his customers relate to him.

His system of giving unbidden discounts to people is still hailed as a pioneering ploy by admiring and envious fellow booksellers. His system of stacking books and overwhelming the book buyer with bewildering choice, was the antithesis of the super neat bookstore. There was no “YA” section in Premier. Or any section in Premier. (But when you asked Shanbhag about this, he was puzzled. “Over there’s the travel section. There’s the children’s section. This is the new arrivals section…”)

Mr Shanbhag also quietly cultivated his best customers. They included authors, publishers and the better known people in town (“influencers” in today’s parlance).

But by his laid back demeanour and quiet mien, he related to everyone.

By his business acumen he always knew his business was to sell books.

And he achieved this by creating a retail environment where the rest of us could enjoy our literary fantasies. And like every good restaurateur who can keep track of dozens of regulars and their likes, dislikes, preferences and previous orders, Shanbhag was the consummate bookseller. He turned Premier into a nationally known brand.

And not without unexpected mischievous humour.

Once, I walked into the store as I always did, to see how The Bangalore Monthly was selling.

A lady walked in at the same time.

Shanbhag looked up, saw the both of us and said, to both of us, at the same time, “Sold out”.

A regular buyer of the magazine, she looked miffed because she did not get her copy.

Of course, I looked pleased that she could not get her copy.

Shanbhag caught this coincidence and did his trademark throw-head-back-and-laugh thing.

The lady looked sharply at him.

I handed her my personal copy and told her it was on the house.

She thanked Mr Shanbhag. Not me.

It was his house after all.

Image source: under CC licence via Google